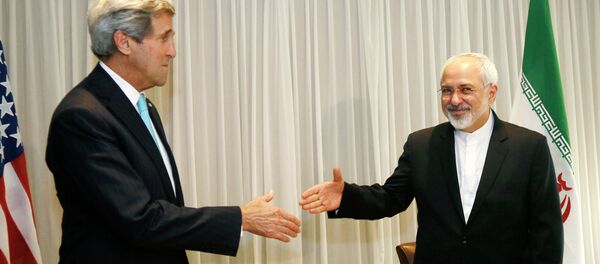

US Secretary of State John Kerry arrived in Switzerland on Sunday, joining negotiations between Iran and the other five major world powers – the UK, China, France, Germany, and Russia. By his side was Ernest J. Moniz, US energy secretary, and both men hoped to come to some kind of an agreement through the talks.

For years, Iran has sought to strengthen its nuclear enrichment capabilities for energy scientific reasons. The West fears that Iran could use enrichment of any kind to develop a nuclear arsenal, and has imposed crippling sanctions on the Islamic Republic.

According to officials speaking anonymously to the Associated Press, the two sides could be willing to compromise. The new framework has several moving parts, and would potentially impose enrichment restrictions for the next 10-20 years, with time off for good behavior, so to speak.

“These were very serious, useful, and constructive discussion,” a senior US official told reporters. “We have made some progress but we still have a long way to go.”

For its role, Iran would agree to decrease its number of enrichment centrifuges from 10,000 to 6,500. While this is still a larger number than the US initially proposed, each would operate at a lower capacity.

The United Nations nuclear agency would be responsible for monitoring Iran’s enrichment centers. If Tehran does stick to the arrangement, the West could begin lifting constraints in the closing years of the deal.

For example, if both sides agree on a 15 year enrichment restriction period, the first 10 years could see strict limits, while the remaining five could see an easing of those controls, if Iran plays along.

“We had serious talks with the P5+1 representatives and especially with the Americans in the past three days,” Foreign Minister Mohammad Javad Zarif told Reuters. “But still there is a long way to reach a final agreement.”

Still, some Iranian officials involved in the negotiations have expressed reluctance to have Iran’s nuclear program hindered. Ali Akbar Salehi, director of the Atomic Energy Organization of Iran, has argued that the Islamic Republic should have industrial-scale enrichment capabilities by 2021, a timeframe seen as unacceptable by the US.

For its part, the US would agree to gradually lift the economic sanctions placed on Tehran. Washington also wants to maintain its goal of ensuring that Iran would be at least a year away from building a nuclear weapon, should it terminate the agreement.

Officials have not given any word on how Iran’s underground enrichment facility at Fordo and the reactor at Arak would work into negotiations.

This is also far from a done deal. While the talks may be showing signs of progress, officials have given no indication that the deal is a sure thing.

“Time is passing,” Kerry told the New York Times on Monday. “We are working.”

While the final outcome of the negotiations may remain unknown, diplomats are racing against an end-of-March deadline which neither side has expressed interest in extending. The White House is anxious to prove to the US Congress that it has made progress. If unconvinced, Congress could implement new sanctions against Iran, a move that could hinder any future negotiations.

Also adding to the complications is the fact that Congress will have to sign off on any proposed agreement. A Republican controlled House of Representatives, deeply distrustful of Iran’s intentions, could make it difficult to get those signatures.

Should a deal be reached, President Obama could lift several of the Iranian sanctions through executive action. Certain restrictions could also be temporarily suspended, but it requires an act of Congress to permanently remove the restrictions.