Between 1933 and 1944, Franklin D. Roosevelt launched a series of fireside chats. The radio addresses gave the American people a direct connection with their president. In 2013, President Obama adopted the idea for the 21st century. Instead of the radio, Obama spoke to his nation through Google. Instead of “fireside chats,” the modern version was rebranded as the slicker, hipper, “Fireside Hangout.” Alternative titles could have just as easily been “Fireside Chill-Sesh” or “Backyard BBQ with Barack and You.”

“This is the most transparent government administration in history,” Obama said.

But according to a new study conducted by the Columbia Journalism Review, this digital outreach was just one example of an administration which has consistently attempted to bypass the US press and communicate with the American public on its own terms. The strategy has proved very effective for one of the most media savvy presidencies in history, but has also created an uncomfortably hostile relationship between President Obama and the journalists tasked with holding him accountable.

“The relationship between the president and the press is more distant than it has been in a half century,” the report reads.

As the report notes, the president gives far fewer press conferences than his predecessors.

Even when Obama does talk to the media, his answers are often long and meandering, offering little time for other questions to be asked. But despite the length of these responses, revelatory news is rarely made.

And as the Fireside Hangout illustrates, the “White House has new tools allowing it to release and manage news on its own schedule and terms.”

On its side of the debate, the Obama administration argues it has limited press access because the media simply isn’t doing its job. Press Secretary Josh Earnest has expressed frustration with the new quick-pace nature of the 24-hour news cycle, and its preference for tweetable buzzwords over substantive reporting.

But the White House, too, has its own Twitter account, and many correspondents have voiced irritation at not being able to accomplish what they see as their core goal: “to explain why the president does what he does.”

“The people who cover the president know him the least,” Peter Baker, White House correspondent for the New York Times, told the Columbia Review. “People ask me all the time, ‘What’s he like?’ As if I knew.”

Baker isn’t the only one. The entire White House press-pool has been in open conflict with the White House. Last September, the Washington Post reported that a number of journalists complained that Obama’s press aides had demanded changes in news articles.

“My view is the White House has no right to touch a pool report,” National Journal writer Tom DeFrank told the Post. “It’s none of their business…They have no right to alter a pool report unilaterally.”

This was followed by a formal complaint made by dozens of White House photographers last November.

“Journalists are routinely being denied the right to photograph or videotape the President while he is performing his official duties,” the complaint read. “As surely as if they were placing a hand over a journalist’s camera lens, officials in this administration are blocking the public from having an independent view of important functions of the Executive Branch of government.”

The administration has also taken several other steps to undermine the idea of a free press.

According to a poll conducted by the Pew Research Center last month, 80% of media figures believed their profession made it more likely that the government collected their data. As many as 64% thought the government has already gathered information on them. Several journalists also expressed fears of communicating with sources electronically.

In 2013, the US Department of Justice was found to be spying on the phone records of Associated Press reporters. The organization called this a “serious interference with AP’s constitutional rights to gather and report news,” according to the New York Times.

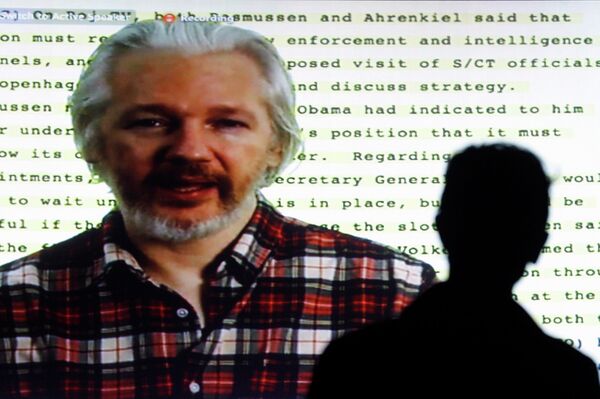

In 2010, the Justice Department was actively considering pressing charges against WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange. As of 2014, the FBI still has “an active and ongoing,” criminal case against Assange, according to court papers leaked to Australian newspaper the Age.

The administration has also made concentrated efforts to crackdown on whistleblowers. 47-year-old Jeffrey Sterling was found guilty of leaking classified material after he revealed details about a botched CIA plan to provide Iran with flawed nuclear weapons blueprints.

Perhaps even more frightening was the US government’s attempt to force James Risen, the New York Times reporter who broke Sterling’s story, to reveal his source. Risen was threatened with jail time, but insisted he would rather go to prison than break his vow of confidentiality.

Another whistleblower, John Kiriakou, was sentenced to 30 months in jail after he confirmed that the US was torturing al-Qaeda prisoners with waterboarding.

And then there’s former NSA contractor Edward Snowden, who is still hiding in Russia. His revelations about the NSA’s spying program proved a monumental lack of transparency within the US government.