US Vice-President Joe Biden is meeting Northern Ireland's First Minister Peter Robinson and Deputy First Minister Martin McGuinness on St Patrick's Day, but the occasion is unlikely to leave much room for celebration. The season of traditional marches is around the corner and both sides are wary of what they may bring.

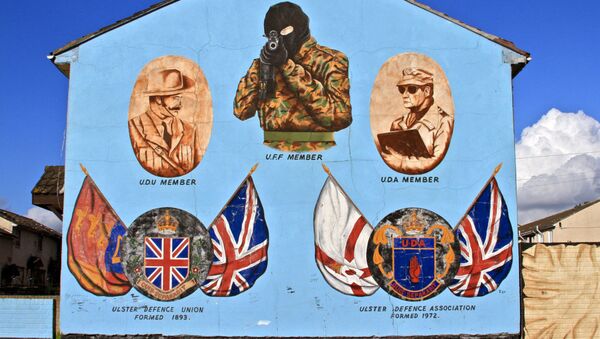

Disagreements between the Unionist and Republican leaders have now been simmering for months and prevented an accord on three main points of contention — parades, flag waving and dealing with the legacy of the Troubles. Earlier this year Robertson branded McGuinness a 'dictator' while McGuinness accused Robertson of 'dancing to the tune of extremists'.

The latest stumbling block has been a welfare reform on which the parties have failed to find common ground, thereby putting the entire power-sharing agreement in jeopardy. The legacy of decades of acute conflict and some 3,500 deaths during the Troubles weighs too heavily on those called upon to live together.

Mediation and Interference

Former US Senator George Mitchell is credited with putting the Northern Ireland peace process on track and securing the Good Friday Agreement of 1998. However, disagreements between the Unionists and Republicans have never disappeared, wrecking the latest mission by US mediator Richard Haass, defying efforts by another US envoy Gary Hart and prompting the need for a real heavyweight, the US Vice-President to intervene.

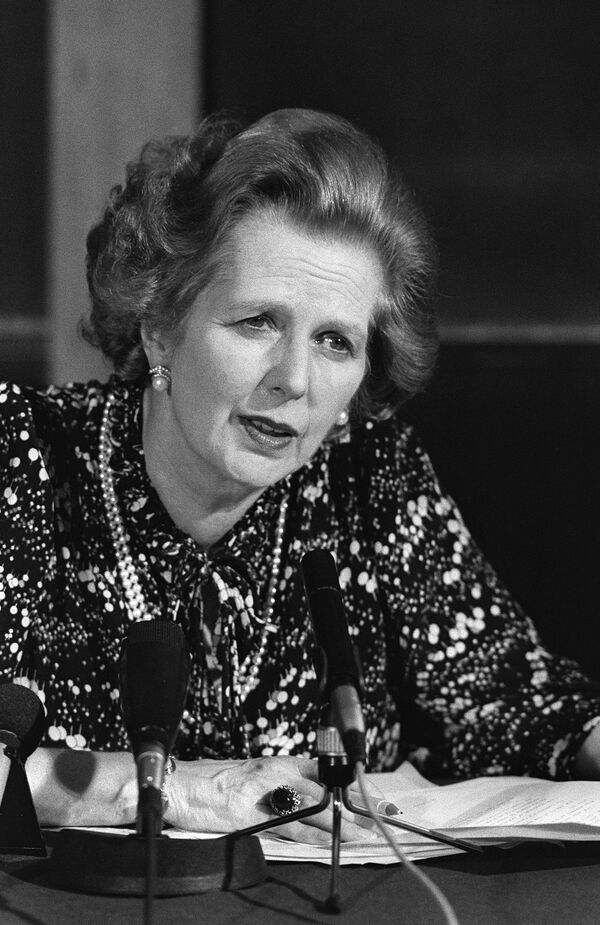

US mediation has more recently been welcomed by both factions in Belfast and by London. But that was not always the case. Documents disclosed several years ago revealed that back in 1979, at the height of the Troubles, Britain's PM Margaret Thatcher was quite incensed by what she saw as American interference in Northern Ireland:

"The Americans must be made to realise that for so long as they continued to finance terrorism, they would be responsible for the deaths of US citizens as well as others."

That was of course a reference to arms smuggled into Northern Ireland from the US in significant quantities until at least the mid 80s. Thatcher was also furious about President Carter's refusal to supply guns to the Royal Ulster Constabulary that year. Another thing that prompted the British PM's wrath was Carter's pointed restraint in reacting to the murder of Lord Mountbatten killed by an IRA bomb in 1979 together with his grandson and a local boy.

In his message on the death of the Queen's cousin and former Viceroy of India, Carter expressed his 'profound sadness'. "President Carter's message is notable for making no reference to the circumstances of Lord Mountbatten's death," a Foreign Office official said then. "There's no mention of murder or terrorism, no condemnation of those who indulge in violence."

Thatcher for Cromwellian Solution

US 'interference' was of course prompted primarily by the Irish roots of many Americans, including those in the higher echelons of power. Another factor must have been America's historical distaste for the British Empire and all empires in general.

Over the years, however, as the US itself acquired unmistakable characteristics of an empire, the latter factor may have morphed into something different, a premise that its involvement is a matter of course and the superpower's inalienable right and even responsibility.

London's acceptance of this state of affairs may stem from a realisation of its own limitations in playing the role of an honest broker in Northern Ireland and from recognition of Washington's constructive role. Another reason could probably be the absence of an Iron Lady — or, indeed, an Iron Lad — at the helm in London.

According to the 1979 notes, Thatcher made a point that:

"Northern Ireland was part of the United Kingdom and she herself would not think of discussing with President Carter, for example, US policy towards their black population."

Mrs Thatcher tried to stem the tide of Irish republicanism with an iron fist, of course. She brought in the army and armed the RUC (they still had some American-made arms despite Carter's refusal). In 1981 she practically condemned ten IRA militants who had begun a hunger strike to starving themselves to death by stripping them of any political status and treating them like common criminals.

According to the British PM, that would not only put an end to the Troubles but would also pacify nationalists who wanted to be united with Ireland. Small wonder that the news of Margaret Thatcher's death in 2013 was met with republican street parties throughout the province.

Since the start of the peace process and the Good Friday Agreement the situation has of course changed dramatically. Violence has subsided and peace has been established, even if tentative and shaky. Meanwhile, Unionist and Republican communities in Northern Irish cities and towns remain divided by tall fences dubbed 'peace walls', an ultimate euphemism.

Thatcherites in Kiev

There are of course some similarities and vast differences between the situation in Northern Ireland and that in Ukraine. The overriding common aspect of both conflict situations is that there are deeply divided communities.

The chasm between East Ukraine and 'mainland' Ukraine is at least as profound as between the Unionist and Republican communities in Northern Ireland. Historical and other reasons notwithstanding, that is a reality one needs to understand to have any hope of at least mitigating the disaster in progress there.

The Kiev authorities — with unconditional support and encouragement from Washington and London — have been using extreme force to subjugate the restive East. Over 5,300 people (a very conservative estimate) have been killed as a result of an iron fist strategy not even Baroness Thatcher could conceive of.

In a chilling parallel, there is a constant refrain from Ukrainian nationalists, to the effect that those in East Ukraine who love Russia so much, should move there. In fact, Crimeans have done just that — but have also taken their land with them.

However fragile and halting the Northern Ireland peace process may be, it is much preferable to the Thatcher recipe. After dozens of years of dealing with it both London and Washington must be painfully aware of the complexities and intricacies of the Northern Ireland quandary. So why do they think they have a quick fix for Ukraine?