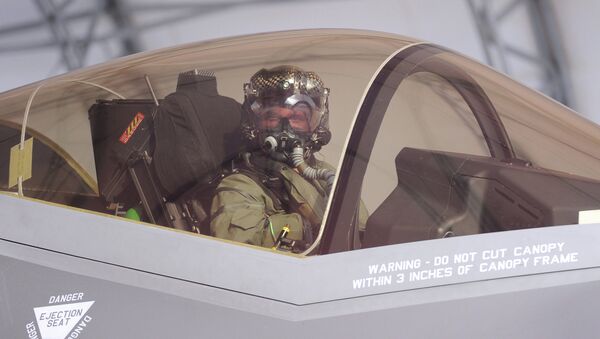

In development since 2001, the F-35 program is expected to cost well over $1 trillion and has yet to achieve even "initial operational capability" for any branch of the military.

— Eli Lake (@EliLake) September 17, 2014

The Navy — unlike the Air Force — currently does not have armed unmanned aerial vehicles (UAV), but Navy Secretary Ray Mabus made it clear that, despite having positive things to say about the F-35, the future is pilotless.

"Unmanned systems, particularly autonomous ones, have to be the new normal in ever-increasing areas," Mabus said at the Navy League’s Sea-Air-Space 2015 Exposition.

"For example, as good as it is, and as much as we need it and look forward to having it in the fleet for many years, the F-35 should be, and almost certainly will be, the last manned strike fighter aircraft the Department of the Navy will ever buy or fly."

All apologies to the Ice Men of the world, but even the best pilots are still a liability, and going unmanned removes that liability, as Mabus explained, inadvertently making a theme of Jerry Bruckheimer's planned Top Gun sequel eerily prescient.

— Rohan Patel (@KingPatel7) March 29, 2014

"With unmanned technology, removing a human from the machine can open up room to experiment with more risk, improve systems faster and get them to the fleet quicker."

To that end, Mabus announced the creation of both a new deputy assistant secretary position and a Navy staff position — N-99 — analogous to the existing surface and air warfare directorates — "so that all aspects of unmanned – in all domains – over, on and under the sea and coming from the sea to operate on land – will be coordinated and championed."

So far, the Navy's UAVs have operated within intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance (ISR), and the department is currently developing their first unmanned carrier-launched aircraft. Their goal is for that aircraft to be able to provide ISR, strike capability and air support in complex war environments.

Similar to the F-35 program itself — which has struggled to incorporate the disparate priorities of various branches of the military — the Navy's Unmanned Carrier-Launched Airborne Surveillance-Strike (UCLASS) program has suffered delays and raised debate about what features should have priority given cost and available technology.

Currently, Boeing, General Atomics, Lockheed Martin and Northrop Grumman are working up different versions of the carrier for the Navy to decide between.

F-35: Over Before It's Even Begun?

While Mabus declares F-35 the last of its kind, the Navy, the Marines, and the Air Force are still waiting for their first crack at deploying the fighters.

— Shi Xian Lee (@FSKrieger22) May 31, 2012

The Marines are first in line, with IOC for their version scheduled for July 2015, but even that is starting to look overly-optimistic. The laundry list of problems with the F-35 — from software to engine troubles — leaves many skeptical that the planes will ever fulfill the promise of being a versatile, technologically cutting-edge replacement for fighters across the military.

— Drunk Predator Drone (@drunkenpredator) April 5, 2014

Among the admissions at the most recent congressional hearing on Tuesday were that the F-35s much-touted software system for monitoring maintenance was indicating false positives 80% of the time when being used to check on the fitness of the jets.

In another blow to the program's reputation, the Defense Department's director of operational testing, Michael Gilmore, testified that the F-35 would never be able to provide the kind of support for ground troops that the already 40-year-old A-10s deliver. Gilmore cited "digital communications deficiencies" as well as faults in the F-35's threat detection systems.

Gilmore's 2014 annual report, released earlier this year, had concluded that despite improvements to the F-35's threat detection system software “fusion of information from own-ship sensors, as well as fusion of information from off-board sensors is still deficient. The Distributed Aperture System continues to exhibit high false-alarm rates and false target tracks, and poor stability performance, even in later versions of software.”

The Armed Services hearing was to review the project's budget and affordability as the Pentagon plans to step up production of F-35s from 24 jets in 2015 to 120 in 2021.

— CR (@KYColC) March 11, 2013

That kind of production push would require an average of $12.7 billion a year for more than 20 years, Michael Sullivan, the GAO’s director for acquisition and sourcing management testified, admitting that “something has to give, and a lot of times it’s quantities.”

The program has already nearly doubled its original budget to $400 billion in spending — making it the most expensive plane in history. And that doesn't take into account the $5 billion or so the military has spent to extend the existing fleets this plane was supposed to replace or the $650 billion or so in maintenance costs the Government Accountability Office has estimated will be necessary, which would bring the total cost to well over $1 trillion over the next few decades.

— Lloyd Rang (@lloydrang) April 27, 2012

Many attribute the difficulties of the program with the overzealous demands from all branches of the military to incorporate features to suit their particular needs all in one plane, with some calling it the Flying Swiss Army Knife. The F-35 is supposed to be a bomber, a fighter, and capable of performing ground support, but some of those capabilities have contradictory needs. Add to it a load of highly complex computer systems and by trying to please everyone, it may end up performing for no one.

— Joe Zilch (@joezilch) April 16, 2015