Researchers looked at earthquake data for the region to develop models "to calculate how often earthquakes are expected to occur in the next year and how hard the ground will likely shake as a result."

— USGS (@USGS) April 23, 2015

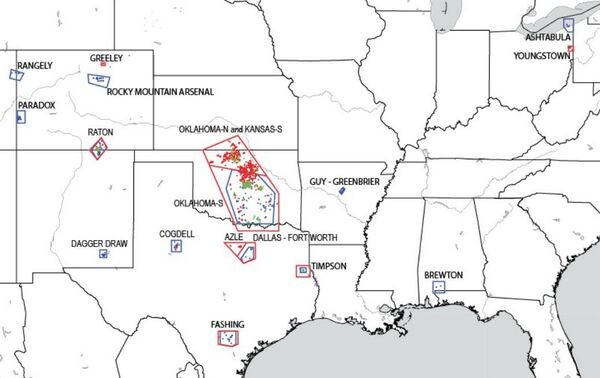

They identified 17 regions that had seen more earthquakes since 2000 and even greater seismic increases since 2009.

Oklahoma in particular has seen a marked increase in seismic activity, as can be seen in the map below, where red dots indicate earthquakes in 2014. The regions the map highlights "are located near deep fluid injection wells or other industrial activities capable of inducing earthquakes," the study said.

"These earthquakes are occurring at a higher rate than ever before and pose a much greater risk to people living nearby," said Mark Petersen, Chief of the USGS National Seismic Hazard Modeling Project

There has been a documented uptick in earthquakes in regions that historically have had little seismic activity such as Alabama, Arkansas, Colorado, Kansas, New Mexico, Ohio, Oklahoma and Texas.

Pressure has been mounting on officials to examine the process of hydraulic fracturing, or "fracking," a process increasingly used in the same areas that are seeing more earthquakes.

In the fracking process, water and chemicals are pumped underground to break up rock formations and release natural gas, creating an enormous amount of wastewater which often, instead of being recycled, is simply injected back into the ground.

As the USGS report explains, the injection of wastewater "'increases the underground pore pressure, which may lubricate nearby faults thereby making earthquakes more likely to occur," adding, however, that "most wastewater disposal wells do not produce felt earthquakes."

But "the picture is very clear" that wastewater injection can activate dormant faults, USGS geophysicist William Ellsworth told the Associated Press.

The connection between the quakes and fracking itself is less clear, and the USGS is cautious, saying that its own studies "suggest that the actual hydraulic fracturing process is only occasionally the direct cause of felt earthquakes."

The oil and gas industry in general has so far claimed that any links between fracking in particular and earthquakes need further study. Oklahoma in particular, which has seen a significant boon to employment and tax revenues with the energy industry boom has been reluctant to recognize a connection.

But the Oklahoma Geological Survey released a report Tuesday that admitted the spike in quakes was “very unlikely to represent a naturally occurring process” that coincided with the simultaneous spike in wastewater injection.

In 2013, earthquakes were occurring in Oklahoma at 70 times the rate pre-2008.

The OGS report is a marked change from even their 2012 study, where they more cautiously concluded that while some quakes could be wastewater related, it was "unlikely that all of the earthquakes can be attributed to human activities."

A 5.6-magnitude earthquake that hit Prague Oklahoma in 2011 — which was linked to local fracking activity — damaged 200 buildings.

— NewsOK Energy (@NewsOKEnergy) April 21, 2015

The increased seismic activity is a new danger in an area used to tornadoes but for whom earthquakes were something that happened only to Californians.

One of the purposes of the USGS study is to be able to incorporate new, man-made seismic activities into its National Seismic Hazard Maps, which "are used in building codes, insurance rates, emergency preparedness plans, and other applications."

Man-made quake activity can change in a given location over a much shorter time frame so the survey is trying to adjust the way it measures and forecasts its hazard assessments to the new seismic conditions. The researchers want to "try to find a way to quantify the associated hazard."

Some recommendations that USGS geophysicists have made for mitigating the seismic effects of oil and gas production are to recycle more wastewater instead of injecting it underground, locating injection sites far from known areas of seismic activity or far from populated areas where damage would be greater. They stop short of condemning the processes wholesale.

"We think society can manage the hazard," Ellsworth told the Los Angeles Times. "We don’t have to stop production of oil and gas, but we think we can do so in a way that will minimize the earthquake hazard."