A series of images was taken at 13 different times spanning 6.5 days, from April 12 to April 18, 2015, when the spacecraft’s distance from Pluto decreased from about 69 million miles [111 million kilometers] to 64 million miles [104 million kilometers].

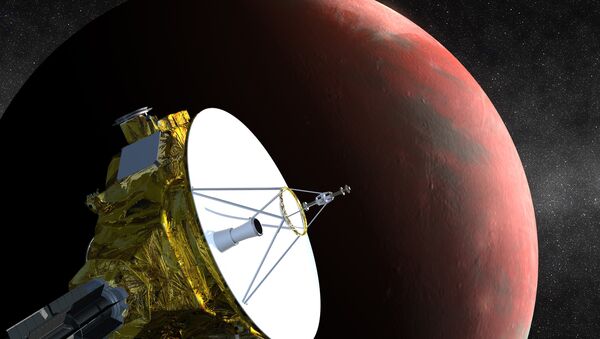

Pluto orbits our sun more than 3 billion miles [about 5 billion kilometers] from Earth, and until now scientists have been unable to see its surface in detail; the New Horizons probe, the fastest ever launched, has traveled a longer time and further away than any space mission in history.

In the images taken by New Horizons' telescopic Long Range Reconnaissance Imager [LORRI] camera, Pluto and its largest satellite Charon are shown rotating around a center-of-mass every 6.4 Earth days, with one pole of Pluto primarily visible, since the planet rotates on its side.

Our best pics of #Pluto yet — and as @NASANewHorizons gets closer, the images only get better! http://t.co/Rp2FHU7E2y pic.twitter.com/OwEzlaqyeV

— NASA New Horizons (@NASANewHorizons) 29 апреля 2015

The above tweet shows images from New Horizons' telescopic Long Range Reconnaissance Imager (LORRI) camera of Pluto and its moon Charon, completing one complete rotation of the system.

This pole "appears to be brighter than the rest of the disk in all the images," report the researchers, who believe the brightness might be caused by a "cap" of highly reflective snow. "The 'snow' in this case is likely to be frozen molecular nitrogen ice," a hypothesis which New Horizons observations will determine definitively in July, when the spacecraft completes its close flyby.

"We can only imagine what surprises will be revealed when New Horizons passes approximately 7,800 miles [12,500 kilometers] above Pluto’s surface this summer," said Hal Weaver, the mission’s project scientist at the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory, where the New Horizons spacecraft was designed and built, and from where the probe is operated.