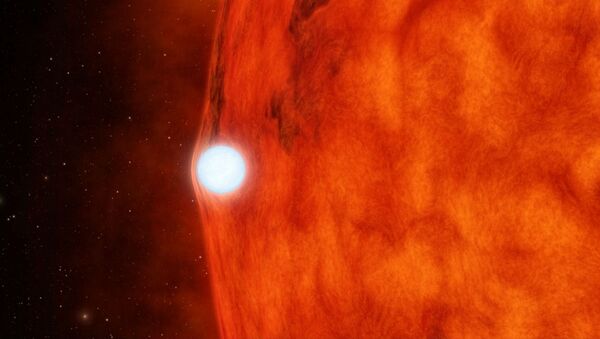

Five hundred light years from Earth floats a small red dwarf known as HATS-6. Emitting only a fraction of the light of our own sun, these kinds of stars are common, but difficult to study because of their dimness.

Which is why it was so surprising when scientists from the Research School of Astrophysics and Astronomy detected a slight softening of its already faint light. That observation was made with small robotic telescopes at the ANU Siding Spring Observatory. To confirm their suspicions, the team called in for assistance from one of the world’s largest observatories, the Magellan Telescope in Chile.

In this way, scientists were able to confirm that the reduction in light had been caused by a passing planet. But measurements indicated that the extraterrestrial body was large. Not the biggest planet ever discovered, but certainly too large to orbit so close to a red dwarf.

"We have found a small star, with a giant planet the size of Jupiter, orbiting very closely," researcher George Zhou said, according to Astronomy Magazine.

So close that the planet makes a complete rotation around HATS-6 once every three days.

The traditional thinking is that planets form from the leftover dust and gas that lingers around stars, as gravity slowly coalesces those small pieces into ever larger masses. But with a small star, there simply isn’t enough leftover material to form large bodies.

"It must have formed further out and migrated in, but our theories can’t explain how this happened," Zhou said.

But the exoplanet’s discovery may open the door for other kinds of studies.

"It’s intriguing how such a small star could form such a big planet. And because it’s so puffed up we can examine its atmosphere more easily than other planets," Zhou said.

"The planet has a similar mass to Saturn, but its radius is similar to Jupiter, so it’s quite a puffed up planet," Zhou said. "Because its host star is so cool it’s not heating the planet up so much, it’s very different from the planets we have observed so far."

Over 1,800 exoplanets have been discovered in the last two decades alone. Which means even if we solve the new questions posed by HATS-6’s massive planet, we’re likely to discover dozens of new, equally mysterious stars, keeping us perpetually in the dark.