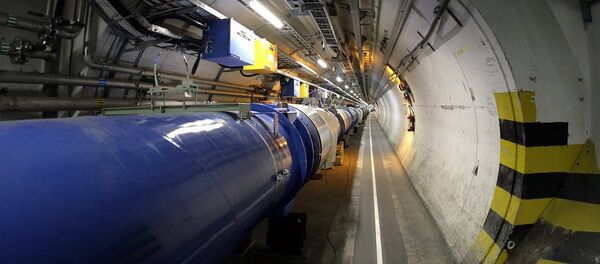

You know the place. The mechanical wonder looped beneath the Swiss Alps which will ultimately suck the entire Earth and universe into a black hole three-tenths the size of a pinprick? Don’t worry, it won’t. But the Large Hadron Collider is performing some equally impressive miracles.

Most recently, it’s slung subatomic particles into each other at ultra-high speeds and created energy measuring 13 trillion electron volts, breaking its own record of eight trillion electron volts.

Breaking that number down becomes a little tricky. To put 13 TeV into perspective, think of an ant. Moving at top speed, your average ant will create roughly the equivalent of one trillion electron volts. So, multiply that by 13, and you have some idea of how much energy we’re talking. The same created by a 10-meter dash held inside an ant farm.

Less impressed? Don’t be, because compared to subatomic particles, ants are large, heavy, and more capable of producing energy. To get a pair of colliding, ultra-light protons to create those kinds of numbers would be like powering all of New York City by throwing two feathers together.

The tiny size of the beams can also present challenges.

"When you accelerate the beams, they actually get quite a lot smaller – so the act of actually getting them to collide inside the detectors is really quite an important technical step," Professor David Newbold, from the University of Bristol, told the BBC.

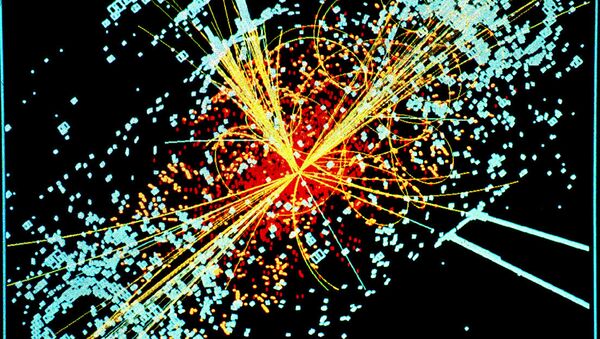

And this is good news for scientists with the European Organization for Nuclear Research (CERN), because ultimately the LHC will be smashing protons day and night, on the hunt for the rarest of rare particles. By observing the collision of protons, scientists can sift through the rapidly evaporating debris to observe the most fundamental building blocks of the universe.

Think of it like this. We know, in this scenario, that chicken pot pie exists, but we have no clue what it’s made of. To solve this problem, you stand with one pie on one side of the room while you’re equally curious cousin stands on the other side of the room with a separate pie. You nod, lower your goggles, and then throw the two together, quickly sifting for ingredients in what remains before the dog licks it up.

And it’s working. The LHC led to the discovery of the long-theorized Higgs Boson, in 2012. (Colloquially known as the "God Particle," physicists typically aren’t big fans of the term, as it implies a more grandiose purpose than the particle actually serves. It also, reportedly, gets its name from Nobel Prize-winning physicist Leon Lederman, who wanted to title his book “The Goddamn Particle,” because of the particle’s elusiveness, before the publishers shortened the phrase to "The God Particle." But anyway…)

The Large Hadron Collider has been shut down for the past two years as engineers install some pretty expansive upgrades. Operations have begun resuming slowly. Last month, scientists began sending beams on casual test-strolls around the collider without any collision, which, frankly, sounds about as exciting as watching an ant walk laps around a doughnut.

But this latest success is a major step, and while the 13 TeV was created through the collision of just two protons, once the LHC is fully operational, scientist will begin smashing beams composed of as many 2,800 protons.

"The special thing about the LHC is not just the energy we can collide the beams at, it’s also the number of collisions per second, which is also higher than any other accelerator in history," Newbold said.

And more collisions mean more chances to find something scientists aren’t even specifically looking for.

"And the best thing that could possibly happen is that we find something that nobody has predicted at all," Professor Dan Tovey, at the University of Sheffield, told the BBC.

"Something completely new and unexpected, which would set off a fresh programme of research for years to come."