On Earth, we have a pretty healthy relationship with the Moon. It does its things, circling the world from a respectable distance, while we do our thing, hurtling around the Sun faster than Usain Bolt. Earth is the star of the show here, and the Moon knows its place.

But moving closer to the vacuum of space, in the Wild West of the solar system, Pluto is facing down a usurper to its throne.

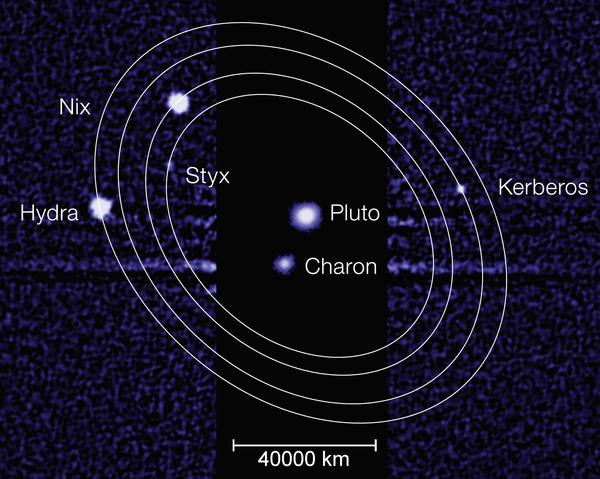

Even though it’s been downgraded, Pluto is still potentially the largest trans-Neptunian object, and as such, it is circled by five moons of its own. Hydra, Nix, Kerberos, and Styx – discovered only as recently as 2012 – seemed to follow pretty traditional orbits. But a new study based on data from the Hubble Space Telescope suggests that Charon, the fifth, may be forcing us to rethink Pluto’s center of gravity.

"Like good children, our moon and most others keep one face focused attentively on their parent planet," said Douglas Hamilton, professor of astronomy at the University of Maryland and co-author of the study published in Nature. "What we’ve learned is that Pluto’s moons are more like ornery teenagers who refuse to follow the rules."

That’s because rather than orbiting around Pluto, the dwarf planet and Charon appear to spin together around a fixed point like a couple of clunky Baryshnikovs. This would suggest that the two actually form a binary planet.

That cosmic foxtrot has implications for the other moons, as well. The binary system creates a gravitational field that’s constantly changing. This means that the rotations of the moons can have unpredictable rotations, spinning one direction, then another, then another.

In short, a few hours on Nix and you’d look as green as Ernest Borgnine after 9 cent shrimp night on the SS Poseidon.

Despite these wild rotations, Pluto’s moons still follow a stable orbit, largely because their combined gravity keeps them all in check.

"The resonant relationship between Nix, Styx, and Hydra makes their orbits more regular and predictable, which prevents them from crashing into one another," Hamilton said. "This is one reason why tiny Pluto is able to have so many moons."

So what does it all mean? While maybe not the most common arrangement in the universe, binary planets do exist, and having one in our own backyard provides an amazing opportunity to understand how they operate.

That knowledge could even help us in the search for life. The erratic rotation of Pluto’s moons likely means they would be unable to develop stable atmospheres, and by extension, life, even if the system was within the habitable zone. If that’s common behavior for bodies orbiting binary planets – or binary systems in general – we may have some idea of where not to waste our time looking for signs of ET.

"We are learning that chaos may be a common trait of binary systems," Hamilton said. "It might even have consequences for life on planets orbiting binary stars."

It may not be a planet anymore, but at least Pluto’s not all alone out there.