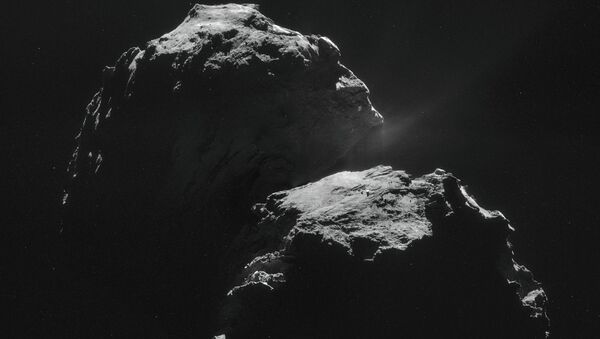

The comet is currently on its approach to the Sun, and will reach its perihelion, the point when it is closest, on 13 August. Then, it will be just 270 million kilometers away from the Sun.

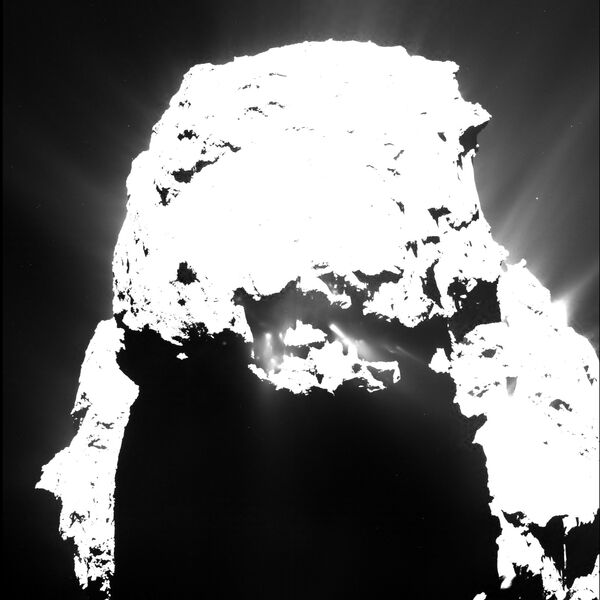

"The solar irradiation is getting more and more intense, the illuminated surface warmer and warmer," explained OSIRIS Principal Investigator Holger Sierks.

"Only recently have we begun to observe dust jets persisting even after sunset."

The Optical, Spectroscopic, and Infrared Remote Imaging System [OSIRIS] is the main imaging system of the Rosetta mission, consisting of two cameras; one to map the nucleus of the comet, and another to map the gas and dust in space around the comet.

The scientists who are operating the Rosetta mission suspect the comet is able to store heat from the Sun for some time in deeper layers below the surface. These deeper layers are suspected to also contain the frozen gases which fuel the comet's activity.

"While the dust covering the comet’s surface cools rapidly after sunset, deeper layers remain warm for a longer period of time," says OSIRIS scientist Xian Shi, who is studying the sunset jets.

The mission, which is due to end in December 2015, is analyzing the comet during its orbit of the sun in a bid to find out more about comets, which are the oldest and most primitive materials in the Solar System and date back to its origin around 4.57 billion years ago. The scientists hope that by analyzing the bodies, more can become known about the origins and evolution of the Solar System itself.