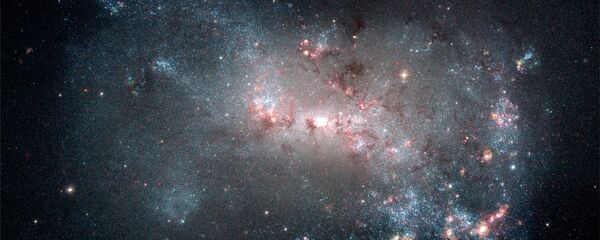

The High Definition Space Telescope (HDST) will be "100 to 1000 times as powerful as the Hubble," according to AURA HDST committee member Michael Shara, and its purpose will be to examine the atmospheres of Earth-like planets deep in the cosmos for signs of life.

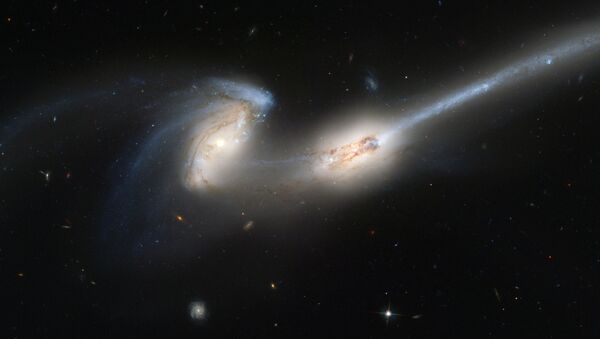

The telescope would be situation in an area known as the second Earth-Sun Lagrange point (L2), roughly one million miles away from Earth, far beyond the moon’s orbit. It would study the universe in ultraviolet, optical, and infrared light using a 39-foot-wide multi-piece mirror, larger than that of both the Hubble and the JWSB, according to Space.com.

"Bigger telescopes see deeper into space and with better detail, period." Tyson told reporters at the panel. "And it’s not just that you will see objects you already know better. Our experience tells us that all-new phenomena, undreamt of, manifest themselves in the face of this higher level of technology. And that is what we’re actually after here – not simply understanding what we already know a little better."

"[The HDST] has the potential to make significant, field-changing discoveries." he added.

The telescope’s much larger mirror would give it greater sensitivity than its predecessors, making it especially useful for the quest to find life in outer space. Using a coronagraph, an instrument that blocks the light from other stars, the HDTV would be able to clearly see planets around the stars they orbit.

Members of the committee compared the HDST’s increased resolution from the Hubble Telescope to that from black-and-white television to today’s modern high definition screens.

— Nat Geo Science (@NatGeoScience) July 7, 2015

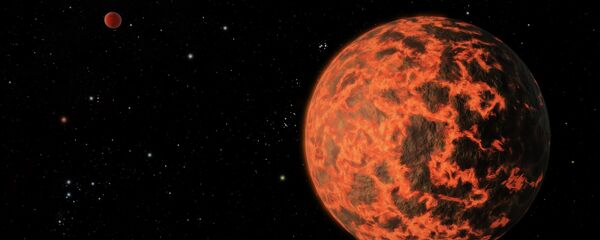

Much of AURA’s report focused on HDST’s mission to identify and study "several dozen" Earth-like planets. The proposal calls for the telescope to study nearly 50 of such planets, and search for any signs of life, ranging from potentially habitable planets to detailed observations of their atmospheres. The study could further help astronomers understand how worlds like our own are formed and when or how life forms can evolve in distant planets.

"The goal is not just to find watery planets with rocky cores," Committee co-chair Julianne Dalcanton said. "We want to find atmospheres that have been shaped by the presence of life."

Sarah Seager, another committee co-chair, said that no other existing or planned telescope would be able to search for signs of life like the HDST. Noting that telescopes like the upcoming JWST have the potential of finding maybe one or two Earth like planets, she stressed the need of having one that can explore dozens and dozens more.

"That’s what this telescope is," Seager said about the HDST.

Saying that it will be a "flagship observatory," committee members stressed that HDST will serve a broader set of purposes other than searching for signs of life. The telescope is slated to launch sometime in the 2030s, and is estimated to cost as much as $9 billion.

The committee’s release of the report comes ahead of the 2020 Astronomy and Astrophysics Decadel, which is published every ten years to make recommendations for the future projects of the astronomical community. Referring to it as a "call to arms," the team unveiled the proposal as a means to plan further push the envelope for space exploration using telescopes after the launch of JSWT.

"If we think about what we want in the sky after the James Webb Space Telescope, we need to start thinking about it now," Dalcanton said. "These are decades-long projects. No mission happens accidentally. AURA thought that it was time to start looking ahead to find a path forward that is scientifically transformative but also technologically possible."