In a crowded presidential field during the 2012 US elections, former House Speaker Newt Gingrich came up with a bold plan to make himself stand out among the crowd. While his competitors debated the economy, foreign policy, and Rick Santorum’s fear of pornography, Gingrich stepped forward to promise the American people his own childhood dream: moon bases.

"By the end of my second term, we will have the first permanent base on the moon, and it will be American," he said.

This received ridicule. But for a number of scientists otherwise less than impressed by the candidate’s stubborn stance on global warming, the idea didn’t sound half bad – even if the timeline was a little too optimistic.

"If the nation dreams big and that percolates its way through society, the dreams are enabled by prowess in science," the renowned face of astrophysics Neil deGrasse Tyson told MSNBC at the time. "I don’t have a problem with Gingrich’s goal."

NASA, it turns out, may have been equally inspired.

Yesterday, the space agency announced it was investing in a new project to colonize Shackleton Crater, a 130-square-mile stretch of lunar real estate encircled by 14,000-foot peaks. While that specific crater was chosen due to the presence of water, there’s still a major problem: that water is frozen, and that crater is cold.

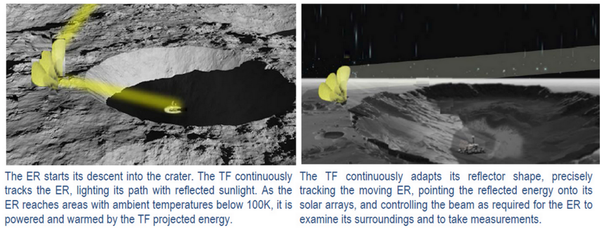

Minus 280 degrees Fahrenheit, to be precise, due to its location on the Moon’s South Pole. To melt that ice, NASA is considering installing a series of large, adjustable, solar reflectors which would travel along the crater’s rim and beam sunlight down into the darkness.

"We will explore this idea, which for the first time points to the possibility to develop a Continuous Solar Power Infrastructure at the South Pole dispersed around [Shackleton Crater], forming a true 'ring of power,'" reads NASA’s project description.

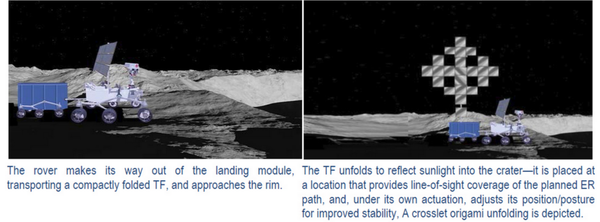

But the reflectors would also serve a second purpose: providing solar power for a fleet of terraforming robots working within the crater. Since the reflectors would follow the sunlight, the robots could work day and night to "extract water, hydrogen, and oxygen."

This process could, in theory, create an “oasis” inside of Shackleton, making it more sustainable for future astronauts.

The funding provides for two years of research, and the team’s next step is designing the reflector. Whatever they come up with, it has to get to the Moon cheaply and practically, so in the interest of portability, the design will need to fold into a 3-foot cube, weigh less than 220 pounds, and maintain a surface area of 10,700 square feet once unfolded.

No sweat, right?

You may have lost the battle, Newt, but it looks like you may have won the war.