Take any rudimentary gaze at a photo of Jupiter, our solar system’s largest planet, and your eye will be drawn to its most distinctive feature. Larger, on its own, than planet Earth, the Great Red Spot is essentially a massive, persistent hurricane. By some estimates, it’s been brewing since 1831. Others suggest it’s as old as 1665, and others still estimate suggest that the storm may be as old as the planet itself.

That should provide some idea of just how difficult exploration of the gas planets can really be. The Great Red Spot isn’t even the strangest weather system we’re aware of. The northern pole of Saturn is enclosed in a perfectly hexagonal vortex, complete with unexplainably abrupt angles.

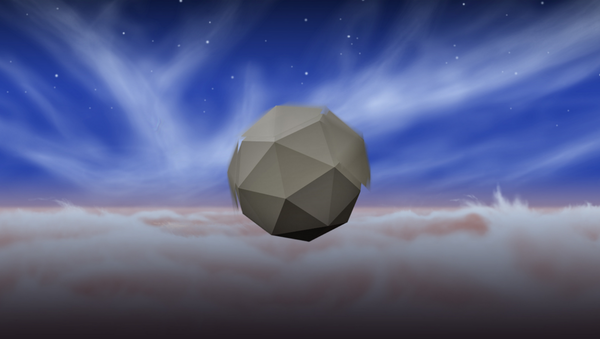

To navigate these environments, NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California is developing a “windbot.” In theory, the robotic aircraft could remain aloft without wings or even its own hot-air balloon system.

How does it fly? By absorbing energy from the planet’s own winds.

"A dandelion seed is great at staying airborne," Adrian Stoica, principal windbot study investigator, said in a statement. "It rotates as it falls, creating lift, which allows it to stay afloat for long time. We’ll be exploring this design in windbot designs."

With $100,000 in funding from NASA’s Innovative Advanced Concepts program, the concept involves rotors attached to various sides of a central probe. Powered by the winds of Jupiter, these rotors would spin independently of the probe, creating lift.

That wind could also power any equipment onboard. A more traditional energy source like nuclear power would prove too heavy for an aircraft with such limited lift. And solar power could be problematic given Jupiter’s long nights.

But wind or kinetic energy could be an ideal fit. Just as your wristwatch absorbs power from the motion of your swaying arm, so too could the windbot gain energy by simply taking advantage of the up and down motions it’s sure to experience in the Jovian atmosphere.

"One could imagine a network of windbots existing for quite a long time on Jupiter or Saturn, sending information about ever-changing weather patterns," Stoica said. "And, of course, what we learn about the atmospheres of other planets enriches our understanding of Earth’s own weather and climate."

Still, the project is in its early stages, and the team isn’t entirely sure that the concept will even work.

"We don’t yet know if this idea is truly feasible," Stoica added. "We’ll do the research to try and find out."