"When I was moved about six months ago with neither my consent nor even informing me, I was deprived of my so-called comfort items," Slahi wrote in an April letter to his attorney.

Slahi alleged that the military "prosecuting team" pursuing confessed terrorist Ahmed al-Darbi "offered to help me on condition to ask the court to lift its order regarding my interrogation."

He said that, in exchange, Guantánamo officials would help him retrieve his legal documents, family photographs and correspondence, including letters from his mother, who died in March 2013.

Slahi's attorney told British newspaper the Guardian that Guantánamo authorities confiscated Slahi's personal items "for the purpose of then using them as a way to get him to ask the court to allow the continued interrogation that the court had ordered ceased in 2010."

In 2009, a federal judge ruled that the government can no longer interrogate Slahi, who had been subject to sleep deprivation, extreme temperatures, stress positions, sexual humiliation, death threats and rape threats to his mother.

The judge ruled the following year that the government could not detain Slahi merely out of concern he could associate with terrorist groups after his release. A government appeal, however, has kept him at Guantánamo.

Slahi's attorneys are hopeful his release could be secured through a Periodic Review Board, a sort of parole hearing. They have accused the government of prolonging Slahi's detention and denying him a Periodic Review Board “for the purpose of interrogation."

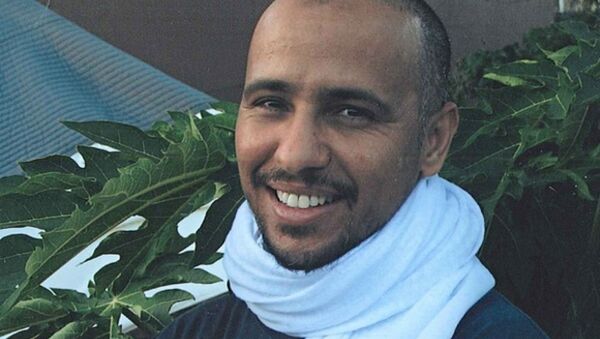

In January, Slahi published a memoir titled "Guantanamo Diary." The book details his torture, extended detention and unlikely rapport with some Guantánamo guards over the 13 years he has been held. It became an international bestseller.