Survivors’ accounts allow historians to reconstruct what happened on that fateful summer day in 1945.

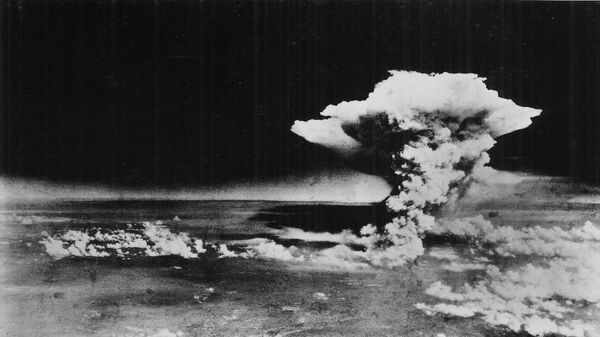

"Nineteen hundred feet over Hiroshima, a 49-foot diameter star began to form, burning with a heat of 300,000 degrees centigrade, consuming the bomb casing and turning it into a random cloud of charged atoms. Touching the ground, the tremendous energy first made the targets radioactive, then destroyed them. Shima Clinic, directly below the atomic nova, simply turned to vapor, leaving behind only two concrete pillars. Anything made of carbon – wood, paper…human beings – became shadows of the hypocenter."

"Little Boy" destroyed two-thirds of the city and instantly killed 80,000 people (40 percent of iroshima’s inhabitants). But tens of thousands of survivors must have envied those who perished right away.

Known as the "ant-walking alligators," they did not look human. Their skin seared from their skulls, leaving them with no eyes and only a small hole for a mouth. They could not speak, and the sound they made was said to be more horrifying than any scream. They did not survive for long and died shortly after the blast, bringing the number of direct casualties of "Little Boy" close to 180,000. Thousands more became hibakusha (explosion-affected), who eventually died from leukemia and other radiation related diseases.

Three days later, on August 9 1945 a second atomic bomb was dropped on the city of Nagasaki, killing between 50,000 and 100,000 people.

The American use of nuclear weapons against Japanese cities has long been a subject of emotional debate around the world. The excuse given by generations of American politicians and historians is that the terrifying effects of the atomic bombings forced Japan’s immediate and unconditional surrender, saving innumerable lives of both the American GIs and Japanese civilians.

However, as early as 1965, historian Gar Alperovitz argued that, although the bombs might have put an end to the war, Japan’s leaders had wanted to surrender anyway, and likely would have done so before the American invasion planned for November 1, 1945. The bombs’ use was, therefore, unnecessary, Alperovitz concluded.

Indeed, during 1945 the US Air Force carried out one of the most devastating bombing campaigns in history. Sixty-six Japanese cities were destroyed by conventional bombs, and only two by atom bombs.

The fire-bombing of Tokyo on March 9-10, 1945 remains the single most destructive attack on a city in the history of war. About 16 square miles of the city were burned out. An estimated 120,000 Japanese lost their lives — the single highest death toll of any bombing raid on a city.

"If you graph the number of people killed in all 68 cities bombed in the summer of 1945, you find that Hiroshima was second in terms of civilian deaths," wrote Ward Wilson, a senior fellow at the British American Security Information Council, for Foreign Policy in 2013. "If you chart the number of square miles destroyed, you find that Hiroshima was fourth. If you chart the percentage of the city destroyed, Hiroshima was 17th. Hiroshima was clearly within the parameters of the conventional attacks carried out that summer."

Japanese General Anami remarked on August 13, 1945 that the atomic bombings were no more menacing than the fire-bombing that Japan had endured for months. If the Japanese were not concerned with city bombing in general or the atomic bombing of Hiroshima in particular, Wilson asks, what were they concerned with? The answer he gives is simple: the Soviet Union.

This assessment was seconded by Tsuyoshi Hasegawa, of the University of California at Santa Barbara, in 2003: "The Soviet entry into the war played a more important role in Japan's decision to surrender than the atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki."

At the Potsdam conference with Truman and Churchill in late July 1945, Stalin informed the two about his readiness to make good on the promise to enter the war against Japan shortly after victory over Germany. The promise was given at the Tehran conference in 1943 in exchange for the Allies' promise to open the Second Front in Europe.

Stalin also told his Western counterparts that Tokyo had approached Moscow asking for mediation to end the war on honorable terms.

But Truman had his own plan. The successful test of the atomic bomb in New Mexico a day before Potsdam started convinced the US president he could end the war without Stalin’s help. Truman had not shared the secret of the Manhattan project with Stalin. It was late in the Potsdam conference that Truman made an oblique reference to the bomb, saying almost in passing that the United States "had a new weapon of unusual destructive force."

To his astonishment, Stalin showed no surprise whatsoever, quipping that he was "glad to hear it." Truman later complained to Churchill that Stalin "never asked a question."

Stalin did not have to. He had known more about the bomb than had Truman, who was only informed of the Manhattan project upon the death of President Roosevelt in April 1945 when he assumed the presidency. In contrast, Stalin had known about it for two years, courtesy of his mole at Los Alamos, Klaus Fuchs. What bothered Stalin was that the Americans had failed to tell him about the bomb. This was a major driver of Stalin’s suspicion of the allies’ true intentions once the war was over.

Another snub to Stalin came in the form of the Potsdam Proclamation, demanding the unconditional surrender of Japan. It was issued by the United States, Britain and China, and Stalin learned about it from a press release.

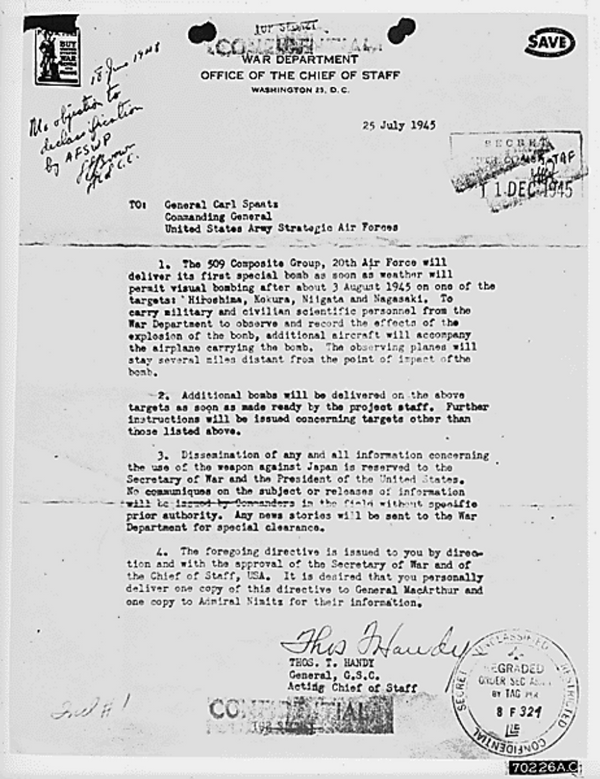

The US-drafted ultimatum was worded in such a way as to leave Tokyo no option but to reject it. It is important to remember, professor Tsuyoshi Hasegawa writes, "that the order to drop the atomic bombs [note the plural] was issued by General Handy, with the prior approval of Stimson [US Secretary of War] and Marshall [Chief of Staff], to General Carl Spaatz, Commander of Army Strategic Air Force, on July 25, one day before the Potsdam Proclamation was issued."

Before the order was given, the Target Committee spent months shortlisting the candidate cities for the first atomic bombing. To better assess the effects of the nuclear weapon they had looked for cities that had never been bombed before. The short list was discussed as early as May 1945 – well before the new weapon was even tested.

Hiroshima came in second — after Kyoto — but Japan’s ancient capital was spared through the personal intervention of War Secretary Henry Stimson, who had fond memories of a pre-war honeymoon in the beautiful city. He was also worried that laying nuclear waste to Japan’s intellectual and spiritual capital would push the Japanese away from the West and into the hands of the Soviet Union, a neutral country at the time. Truman seemed to take away from Stimson’s arguments that Kyoto was not as important a military target as Hiroshima. He wrote in his diary that he agreed with Stimson that the "target will be a purely military one." However, had Hiroshima been an important military target it would have been most probably bombed before the Target Committee was even set up. Thus, through a terrible misconception, Truman consigned the civilians of Hiroshima to obliteration.

The report of the Hiroshima bombing reached Truman on the USS Augusta on his way back to the United States. He could not hide his excitement, and exclaimed, jumping to his feet: "This is the greatest thing in history."

But the bombing of Hiroshima did not immediately lead to Japan’s acceptance of the Potsdam Proclamation. The day after the bombing, Foreign Minister Shigenori Togo sent a telegram to Ambassador Naotaki Sato in Moscow, enquiring about Moscow’s response to Tokyo’s earlier request for mediation. Only after the Soviet Union declared war on Japan on August 9 1945, the all-powerful war party in Tokyo realized the futility of any further resistance.

There are competing theories as why the Americans wanted to drop the atomic bombs: to pip the Soviet Union to the post in ending the Pacific War and enjoying its spoils; to demonstrate their newly acquired exceptional power to Stalin; or to test the new weapon in real-life conditions. Whatever the reason, it was the civilians of Hiroshima and Nagasaki who paid the terrible price for what President Obama calls "American exceptionalism."