Putin has made his "most audacious land grab bid yet," screamed the Daily Express. Russia launches "Arctic land grab," shouted the Mail Online. "Move over Santa: Putin claims the North Pole" wrote the Fiscal Times, before suggesting that polar bears might soon see "little green men" moving in.

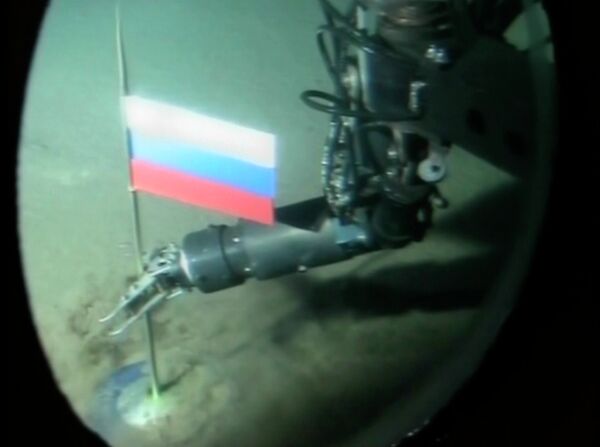

Conservative blog, the Washington Free Beacon got it completely wrong, reporting that along with its bid, Russia had just planted its flag on the ocean floor — a purely symbolic move by Russia that actually happened in 2007.

To be fair, most of the pieces did then grudgingly explain that a number of other countries have also made claims to parts of the Arctic.

But what is immediately obvious is that the vast majority of headlines framed the issue in such a way that the uninformed reader is led to believe that Russia’s claim is something provocative or unusual. Indeed some of the headlines look like they could have been copied and pasted straight out of a NATO press release.

In an age where clicks are king, headlines need to be attention-grabbing — but there is a difference between attention-grabbing and intentionally misleading, as seems to be the standard with much Russia-related content coming from Western media these days.

Add to that this recent research pointing to the fact that about 60 percent of Americans "don’t read beyond the headline" — and you can see why this matters. Dramatic and misleading framing does more to provoke unwarranted outrage than to inform. The result is an inevitable dumbing down of the conversation, and nowhere is that dumbing down more blatant than in the realm of geopolitics.

Geopolitics of the North Pole

Another headline, from the Washington Times, claimed that Russia was "demanding the North Pole" while "still digesting its meal of Crimea".

But let’s instead digest some facts for a second.

The North Pole and its surrounding Arctic waters do not belong to any one nation. Russia is one of five countries that have made claims to various swathes of the territory, the others being the United States, Canada, Denmark and Norway.

According to the 1982 UN Convention on the Law of the Sea — UNCLOS — coastal countries have the rights to marine resources up to 200 nautical miles offshore. That constitutes their exclusive economic zone. UNCLOS allows some countries to expand their claim further than that — but they must provide strong proof that their continental shelf extends beyond their economic zone.

This has led to some verbal spats between the five countries with claims on the territory — unsurprisingly, given that it’s been estimated that about 13 percent of the world’s undiscovered conventional oil resources and 30 percent of undiscovered gas resources could lie in the region.

Russia has claimed space covering an area of about 1.2 million square kilometers, 350 nautical miles from its coast. A similar claim was made by Moscow in 2002 but was turned down due to lack of scientific support. This time around, Russian scientists believe they have ample data to back up their claim.

There is nothing new or unusual about this — it is part of an ongoing (and legal) battle to control coveted resources as melting ice makes them more accessible.

Surprisingly, some of the fairest coverage on the issue this week has come from Canada — unusual given that Ottawa has been neither very diplomatic, nor restrained in its dealings with Moscow of late.

In actual fact, Russia’s bid represents a "soft line" on the issue, UK-based expert Mikå Mered told the Canadian newspaper, Nunatsiaq News.

Mered, a consultant with Polarisk, told the newspaper that there was nothing surprising in Russia’s latest submission — noting in particular that Russia did not claim the seabed beyond the geographic North Pole, as Denmark did last year.

That shows that Russia “doesn’t want to heat up Arctic discussions at this point,” he said, adding that Moscow would not want to scare away investors by making a move that would be seen as provocative.

No Cause for Hysteria

Michael Byers, Canada Research Chair in Global Politics and International Law at the University of British Columbia, told the Toronto Star that he "certainly wasn’t expecting" Russia to "behave so very well" where the Arctic is concerned. He said:

"Russia is following the rules and has made a very restrained submission."

It is unclear what exactly Byers expected, but his premature assumption of bad behavior is evidence enough that Western media’s anti-Russia campaign is having a real effect.

The fairer coverage from Canada is likely due less to any desire to present Russia in a decent light and more to do with the fact that Canada will not want to be left looking like the unreasonable party in any negotiations it may have to enter into with Moscow.

An unreasonable approach from Canada would leave Prime Minister Stephen Harper’s government in an undesirable position and could potentially cause divisions between Ottawa and Washington, who themselves dispute ownership of the Beaufort Sea. Already, the US has, according to reports, chastised Ottawa for making events in Ukraine an issue at an Arctic Council meeting last spring.

The bottom line is that Russia is acting within its rights and according to international law. Its most recent Arctic pitch also clearly states that it is willing to abide by the results of the international process. No cause for hysteria.

There is a dangerous dearth of balanced Western reportage on Russia of late. Let’s not extend that to the North Pole.