"It might sound contradictory, but finding such a small, large black hole is very important," said Vivienne Baldassare of the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, the lead author of the paper detailing the results, called "A ~50,000 solar mass black hole in the nucleus of RGG 118," and published in the Astrophysical Journal Letters.

"We can use observations of the lightest supermassive black holes to better understand how black holes of different sizes grow," she added.

The team of astronomers from the University of Michigan and Princeton University used NASA's Chandra X-ray Observatory and the 6.5-meter Clay Telescope in Chile to identify the black hole, which they hope will provide a clue to how larger black holes formed along with their host galaxies 13 billion years or more in the past, when the Universe was very young.

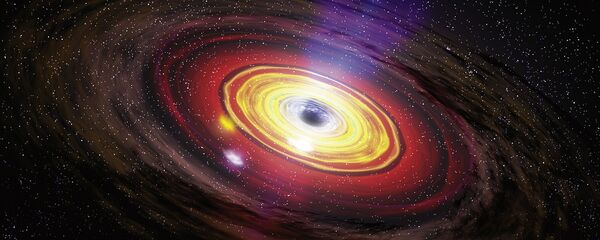

The astronomers estimate that the supermassive black hole in RGG 118 is about 50,000 times the mass of our Sun, yet nearly 100 times less massive than the supermassive black hole found in the center of the Milky Way.

It is less than half the mass of the previous smallest black hole at the center of a galaxy, and also about 200,000 times less massive than the heaviest black holes found in the centers of other galaxies.

The researchers estimated the mass of the black hole by studying the motion of cool gas near the center of the galaxy using visible light data from the Clay Telescope, and used the Chandra data to measure the brightness of hot gas around the black hole in the X-ray band.

X-ray luminosity indicates the rate at which the black hole is taking in matter. RGG 118's black hole is consuming material at one percent the maximum rate, which matches the properties of other supermassive black holes.

"This little supermassive black hole behaves very much like its bigger, and in some cases much bigger, cousins," said co-author Amy Reines, from the University of Michigan. "This tells us black holes grow in a similar way, no matter what their size."

"We have two main ideas for how these supermassive black holes are born," said Elena Gallo of the University of Michigan, another co-author. "This black hole in RGG 118 is serving as a proxy for those in the very early universe and ultimately may help us decide which of the two is right."

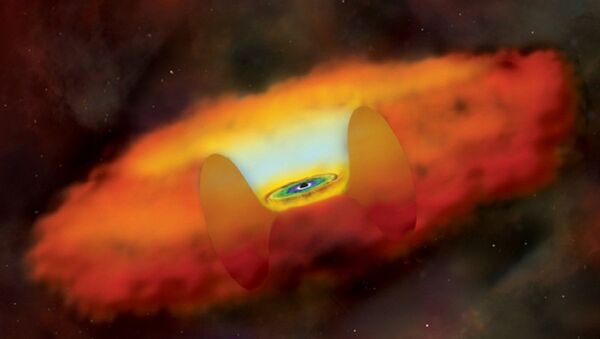

Some astronomers hypothesize that supermassive black holes may form when a large cloud of gas, with a mass of about 10,000 to 100,000 times that of the sun, collapses into a black hole; many of these black hole seeds are thought to then merge to form much larger supermassive black holes.

Another theory is that a supermassive black hole seed could come from a giant star, about 100 times the sun’s mass, that ultimately forms into a black hole after it runs out of fuel and collapses.