First there was the Cambridge Four – a Soviet spy ring at the top echelons of British intelligence, comprised of Cambridge graduates (Philby, Burgess, Maclean, Blunt). Then it became the Cambridge Five with the unmasking of another Cambridge alumni (Cairncross). And now, ladies and gentlemen, please welcome the sixth member of the club!

Although Cedric Belfrage was not directly linked to the Philby circle he went to the same university and spied for the Soviet Union almost in unison with the "magnificent five." While at Cambridge he embarked on a successful literary career. By the 1930-s he became UK’s best paid film critic thanks to his interviews with the Hollywood movie stars, and moved to Los Angeles. A British police report in his declassified dossier says he had a “mild interest in left-wing affairs”. In 1936 Belfrage visited the Soviet Union and was bowled over by Soviet films like The Circus, a story of a black boy rescued from American racists and enjoying a happy life in the USSR. Upon his return to the States he actively engaged with the US Communist party.

In June, 1940, Churchill appointed William Stephenson as Head of the British Security Coordination, an umbrella for all British secret intelligence organizations to maximize their war effort. While in Britain they retained their management and procedures, in the Americas Stephenson ran them all. It was his job to coordinate British secret operations with the Americans, including exchanging top secret intelligence. Churchill had full confidence in Stephenson telling him "you are to be my personal representative in the United States. I will ensure that you have the full support of all the resources at my command."

With the agreement of President Roosevelt and the FBI boss Edgar Hoover, Stephenson and his deputy Charles Howard Ellis set up shop under the guise of a British Passport Office at the Rockefeller Center in New York City. They recruited, among other well-known intellectuals, Cedric Belfrage. It is unclear from the MI5 file whether Belfrage had already been a Soviet agent or was spotted and recruited after he joined BSC.

However the file contains detailed accounts of the kind of services Belfrage rendered to Moscow.

"Belfrage is known to have supplied [Jacob] Golos [a Soviet master spy in North America]… with a report apparently emanating from Scotland Yard which was a treatise on espionage agents. This work dealt with a type of people who might be employed for this sort of work, the precautions which should be taken to elude or determine whether or not a person was being surveilled.

Also contained in this article was a contribution by some prominent burglars in England who apparently had submitted certain techniques of surreptitiously opening safes, doors, locks, and other protective devices."

According to the file Belfrage also relayed to Moscow information on British policy in the Middle East and in the Balkans, where pro-Western and pro-Soviet partisans were pitted against each other. His boss Stephenson let him in on his conversations with Churchill regarding the opening of the Second Front in Europe. Churchill and Roosevelt were playing a stalling tactic with Stalin to keep him in the war by promising to open the Second Front as early as 1942 but in reality they were thinking of 1944. This information relayed to Stalin made him suspicious of the real motives of his Western allies.

Commenting on the release of the Belfrage papers, the official historian of MI5 Professor Christopher Andrew said:

"Belfrage’s Soviet handlers praised the intelligence from BSC files as 'extremely valuable'…Though Moscow has released some of Philby’s KGB file, however, it has revealed nothing about Belfrage."

Which may say something about his importance, at least during the war years.

Belfrage worked for BSC from 1941 to 1943 and then returned to Europe to apply for a job with another British secretive organisation – the Political Warfare Executive. Given his left-wing leanings a request for clearance was sent to Scotland Yard’s Special Branch. The MI5 file contains a terse note: "no objection to his employment."

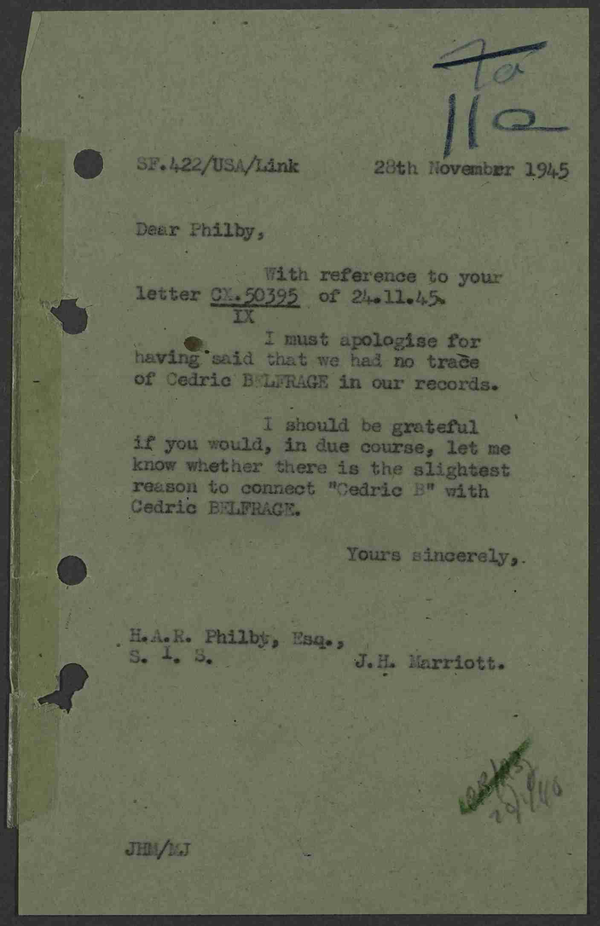

Yet, when Belfrage returned to the United States in 1945 he fell under suspicion from the FBI. His file contains an extremely detailed account of his meetings with leading American communists as well as with suspected Soviet spies, and reports about his illegal activities by "highly valuable" sources whose names are redacted.

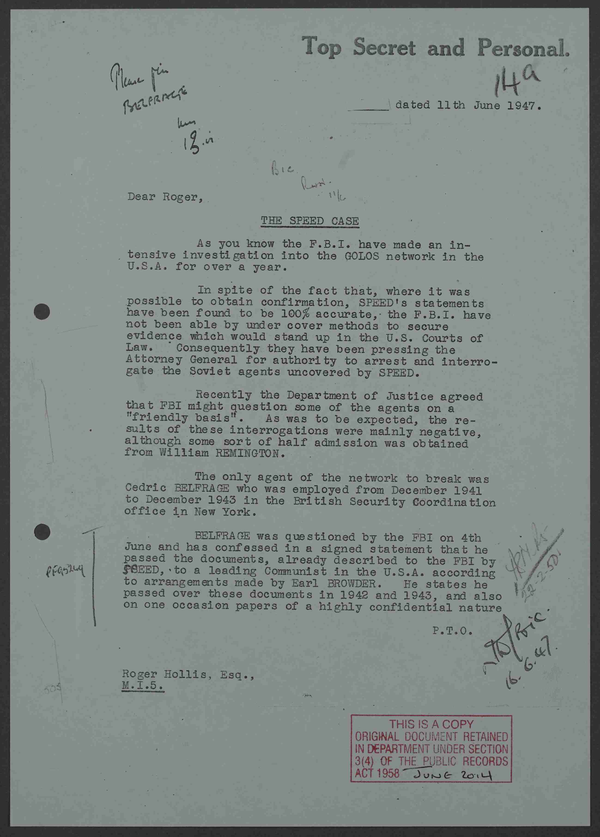

However, one of those sources, Elizabeth Bentley, a former Soviet agent herself came to the fore during a secret hearing before a Grand Jury that looked at a Soviet spy ring in the USA. Belfrage was not the prime suspect in that particular case, but the prospect of the public exposure of the BSC’s failure to figure him out sent the shivers down the spines in London.

The hearing was to drag on for four months between June and September 1947, and a British Embassy cable to London lamented: "As Belfrage falls into the category of miscellaneous agents who will be dealt with last, I am afraid we may have to sit on this powder barrel for many months."

In his examination by FBI Belfrage professed a strict loyalty to the British Secret Intelligence Service and declined to say anything that might reveal SIS’s activities in the States.

He also maintained that the material which he has admitted passing to American Communist contacts and Jacob Golos was not a product of espionage. He claimed that he had been recommended by his SIS superiors to establish outside contacts on a quid pro quo basis, and that he therefore handed over SIS documents in the hope of a useful return.

The American were reluctant to prosecute him since the documents he handed over to Soviet contacts "were the property of the British Government." The file makes a fascinating reading of how the two nations’ secret services that were supposed to cooperate extremely closely were playing political ping pong that sapped their effectiveness. Eventually the Americans deported him on a charge of being a covert Communist levelled at him by the infamous Committee on Un-American Activities of the US Congress.

Later, the US-British Venona project that deciphered Soviet intelligence correspondence did corroborate the spying accusations against Belfrage, but the British were not keen on "revisiting something that has lapsed."

It is interesting to note that Belfrage’s case in the 1940-1950-s was dealt with by Sir Roger Hollis and Sir Michael Hanley, both future bosses of MI5. Both were suspected of being Soviet agents themselves and both were eventually cleared.

Will the voluminous Belfrage file shed new light on their motives, or were they so embarrassed by the multiple failings of the British Secret Service that preferred to sweep the story under the carpet?