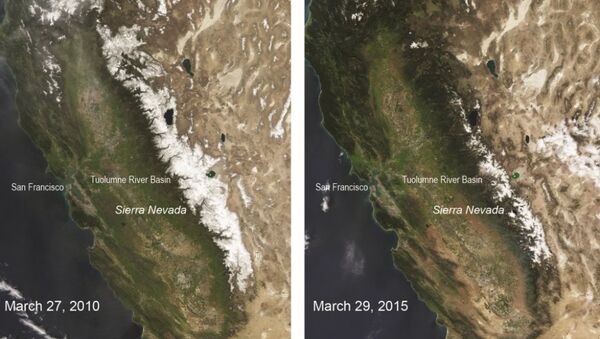

California state officials visited the Sierra Nevada mountain range on April 1 to measure the amount of snow that had accumulated on the slopes during the winter. They found endless patches of dead, dry brown grass.

Six percent.

That is the amount of snow, of normal levels, that the Sierra Nevadas had at the end of the winter season in 2015, according to a new study published in Nature Climate Change.

Most of California’s precipitation comes during the winter months, especially in the Sierra Nevada range, which relies on typically heavy snowfall to pack the mountains. During the summer months, the snowmelt tops off reservoirs with water. However, this year’s almost complete dearth of snowfall compounded the woeful rainfall of previous years, and has left California a delicate, dry tinderbox that sparks increasingly frequent wildfires.

Add the bottling of other California water resources by companies like Nestle, along with gas fracking companies using up huge quantities of water that in the end become polluted and poison local aquifers, it looks as if California is nearing a calamitous precipice. But the intersectional factor exacerbating the problem today — this winter's abnormal warmth.

With global warming expected to raise temperatures even more, the problem is extreme.

“The two coinciding was what really made this such an extreme event,” said Trouet of the heat and drought.

California has so much precipitation to catch up on, even when the state does once again see a normal amount of rain, it won’t be enough unless it is sustained enough to replace the snowpack.

“We need to rethink the way we manage the water system now,” said Peter Gleick, president of the water policy-focused Pacific Institute. “There’s not enough water to do what we want. An El Niño is not going to stop this longer-term trend toward diminished snowpack.”