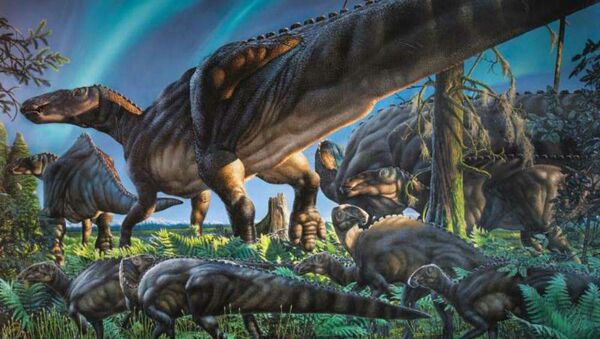

The animal was of the Hadrosaur family of duck-billed dinosaur that roamed in herds, said Pat Duckenmiller, the earth sciences curator at the museum at UAF.

The researchers say that during the Cretaceous period, when the rock was deposited around the dinosaur approximately 69 million years ago, Alaska’s climate was much warmer than it is now, but the dinosaurs still lived in darkness for months and likely experienced winters.

The dinosaur is named Ugrunaaluk kuukpikensis, the Alaskan Inupiaq name for “ancient grazer.” Similar Ugrunaaluk fossils across Canada and Montana have been found previously lumped in with the Edmontosaurus, but the findings in Alaska led the researchers to determine Ugrunaaluk was a whole different species entirely. By plotting out growth trajectories of the mouth bones of the Alaskan fossils and comparing them to the lower Canadian Edmontosaurs, they were able to confirm the difference.

Most of Ugrunaaluk’s fossils were found in the Prince Creek Formation of the Liscomb Bone Bed on the Colville river, more than 300 miles northwest of Fairbanks.

Some disaster took out this large herd of Ugrunaaluk.

“It appears that a herd of young animals was killed suddenly, wiping out mostly one similar-aged population to create this deposit,” said Druckenmiller.

Ugrunaaluk grew to be up to 30 feet long, with hundreds of teeth to help them chew coase vegetation. They walked primarily on their hind legs but also on all fours, according to Druckenmiller.

Paleontologists are working to name at least a dozen more dinosaurs from fossils found on Alaska’s North Slope.

UAF student Hirotsugu Mori completed his doctoral work on the species, and Florida State University paleobiologist Gregory Erickson specialized in the bone and tooth histology and co-published his findings with Mori in the “Acta Palaentologica Polonica” quarterly paleontology journal.