A naturalized British citizen born in Lebanon, the United States government was already actively monitoring Bilal el-Berjawi when he traveled to Somalia in 2006. The Pentagon suspected him of attending a terrorist training camp of the Mujahideen, suspicions that were later confirmed by a martyrdom biography posted on jihadi internet forums.

Berjawi returned to London to control "the collection of funds and its delivery" to the terrorist organization, according to the biography.

"That’s when I realized myself I was starting to be followed," Berjawi said during an interview conducted with human rights group CAGE in 2009. "I would see someone – the same person – following me, wherever I was. The same car – I actually even memorized the number plate."

That sense of uneasiness didn’t end in London. During a trip to Kenya in 2009, Berjawi was briefly detained in the Mombasa airport before being allowed into the country. In the days that followed, he felt he was being tailed by a man he didn’t recognize.

"Where I go to eat, whatever safari park we go to, he’s always there on his phone," Berjawi told CAGE. "When I stop, he stops; when I walk, he walks."

Eventually, Berjawi was apprehended by Kenyan authorities, seemingly on behalf of the British government. While he was never charged with a crime, he was interrogated, accused of being an al Qaeda suicide bomber, threatened with rape, and put through mock executions.

"They just threw us out the car in the forest, and we heard 'tchck-tchck' – you know, the noise was there, and then I’d feel a gun to the back of my head, like that, but…nothing," he said in 2009. "Then they’d just all laugh, pick us back up, throw us back into the car, then they’d drive again."

Released and flown back to England by authorities, Berjawi said that he continued to be harassed by MI5.

"I don’t want to be harassed, followed – I feel intimidated, I’ve got a lot of side effects, you know," he said. "My friends have been scared away from me because they’ve been approached. I feel isolated…It’s becoming a bit too much."

A Shot in the Dark

Three years later, Berjawi was dead. Targeted through a cellphone signal – potentially from a Nokia planted in the vehicle by the CIA, according to one informant – he was shot by a US drone while traveling north of Mogadishu.

But how did a UK citizen come to be covertly assassinated by a British ally.

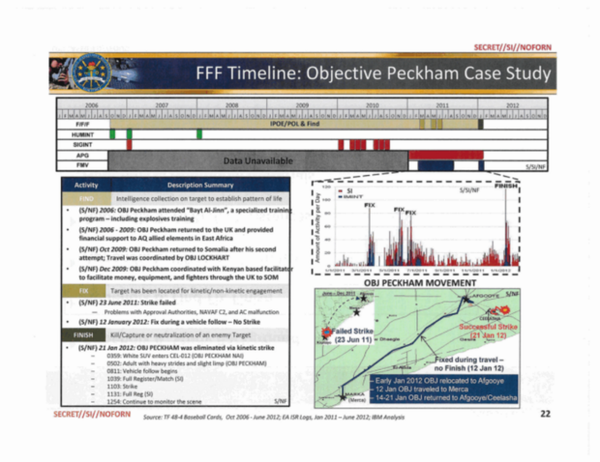

In 2010, Berjawi had his citizenship revoked under the British Nationality Act. It’s unclear if that decision came at the request of Washington, but the secret Pentagon study leaked to the Intercept shows that Berjawi had been placed on a "find, fix, finish," list.

On this "capture or kill" list, Berjawi was given the codename "Objective Peckham."

Given the US government’s constant tracking of his whereabouts, the "capture" option should have been entirely feasible. Intelligence agencies were fully aware of his movements between the United Kingdom and Somalia and Kenya. Berjawi’s wife and two children also lived in London, making his death 4,000 miles away – rather than apprehension – seemingly unnecessary.

But human rights groups also point to the British government’s complicity in the matter – a complicity that is not limited to the case of Objective Peckham.

"If the UK government had any role in these men’s deaths – including revocation of their citizenship to facilitate extra-judicial killing – then the public has a right to know," Kat Craig, a lawyer with Reprieve, told the Intercept.

"Our government cannot be involved in secret executions. If people are accused of wrongdoing they should be brought before a court and tried. That is what it means to live in a democracy that adheres to the rule of law."

According to the Bureau of Investigative Journalism, at least 27 people have their British citizenship revoked in a similar matter. Those decisions, based on national security concerns, are made by a single government minister, and based on evidence which cannot be publicly disclosed for security reasons.

At least ten British citizens have been targeted in drone attacks. While most of those were conducted by the United States, the Royal Air Force began launching its own covert assassinations in September.