Nikolai Gorshkov — The legendary Commander Lionel ‘Buster’ Crabb, OBE, a quintessentially English underwater daredevil of WWII fame, might have been an inspiration for Ian Fleming’s James Bond, but the infamous affair of April 1956, named after him, looks more like being lifted from Graham Greene’s or John Le Carre’s far less glamorous spy stories.

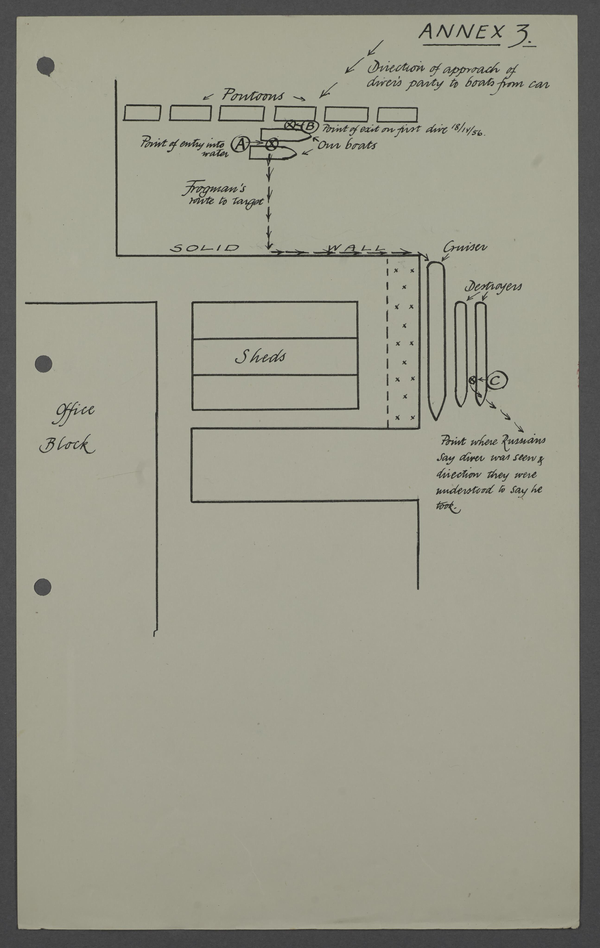

On the early morning of 19 April 1956 Commander Crabb donned his Italian dry suit, attached a brand new spy camera and quietly slipped into the murky waters of the Portsmouth harbor, not far away from the jetty where three Soviet warships were berthed. He was never seen again.

Those were not ordinary warships. They had brought to Britain Nikita Khrushchev on a goodwill visit. It was the first trip of the new Soviet leader (after Stalin’s death three years earlier) to a leading Western country, and was meant to be a breakthrough in the Cold War stand-off. Instead it turned into a public relations disaster.

Khrushchev’s visit to the UK just a month after his shattering denunciation of Stalin’s crimes was a perfect opportunity for the West to gauge the mood in Moscow and look for possible common ground.

Instead the visit was seen in London, the Cabinet files reveal, as a perfect opportunity to spy on the Soviet delegation and the ships that had brought them in.

The files contain an impressive shopping list presented by the Royal Navy, MI5 and SIS to the government, including: bugging the Soviet delegation residence at the Claridges, microphones in cars and providing MI5 “interpreters” to the top members of the delegation. The Admiralty was most interested in the characteristics of the Ordzhonikindze cruiser, the latest and fastest in the Soviet Navy, that had brought Khrushchev to Portsmouth. Most of the proposed operations were rejected by the Prime Minister Anthony Eden for fear of a diplomatic scandal if exposed. Regarding the proposed underwater inspection of the cruiser by Navy divers Eden expressly said that nothing of the kind should be undertaken against the visiting ships.However, SIS found a way around the ban by engaging the retired veteran frogman “Buster” Crabb — with fatal consequences.

The ensuing scandal was so intense, and the mystery of Crabb’s disappearance so deep that the files were to remain classified for a hundred years.

Yet, there has been a trickle of material – either through partial declassification of files or FOI requests.‘While the files don’t solve the mystery of exactly how Cdr Crabb met his death, says Mark Dunton, contemporary records specialist at the National Archives, they lay bare all of the blunders surrounding that operation in its entirety for the first time.’

The files reveal the hot potato syndrome and near panic endured by the top people in the Foreign Office, the Admiralty, SIS and Naval Intelligence. All concerned presumed that clearance had been sought and obtained by the other department, or that somebody else would take the responsibility for the bungled operation and tell Ministers.

The immediate concern was to keep the story from the press. MI6 felt that ‘if Admiralty could bring pressure to bear on any newspaper making enquiries it might damp the affair down”. Frantic efforts were made to cover up the story, including “an unfortunate” decision to tear off pages from Sally Port Hotel guest register where Commander Crabb and his MI6 minder stayed the night before the fatal dive. But soon all the rooms in the hotel were taken by nosy journalists.

The Head of MI5 Sir Roger Hollis said in his response to the enquiry: “the chief risk against which one had to plan in mounting clandestine operations in this country was not the enemy or the object of the intelligence, but the British press”.

However, the biggest fear was that Commander Crabb might have been seized, dead or alive, by the Russians and could be used to embarrass the government.

‘At this stage, the possible explanations for Crabb’s loss seemed to be the following: (a) that he had been observed by the Russians and taken aboard alive; (b) that he had been destroyed by Russian counter measures and that his body was either (i) aboard the Russian ship or (ii) still in the water; (c) that he had been the victim of a natural mishap and that his body was still in the water.’

That the Soviets had Crabb’s body was deemed as ‘by no means impossible’.

The fate of the legendary diver did not appear to be of much concern in itself: ‘The next consideration was the manner in which the body might come to light.

‘If it was aboard the Russian ship, they might produce it for propaganda purposes at an opportune moment either dead or alive, or they might dispose of it after leaving Portsmouth.

‘It was apparent that if the Russians did indeed have the body, no action that we could take in advance could stave off disaster if they chose to reveal the fact.’

The Russians, however, behaved like polite guests should – registering the fact that they had spotted the frogman near their warships but not creating any fuss. They had been tipped off about Crabb’s mission and knew that no harm to the ships was intended. When Khrushchev made a reference to the affair at a dinner, his hosts did not even understand what he was talking about since they were kept in the dark by their subordinates until the Russians left. As head of MI6 noted “it should be realized that Ministers had never hitherto wished to enter significantly into the affairs” of his organization. Sir Edward Bridges whom Anthony Eden asked to conduct an enquiry as soon as he heard of the cover up summed it up very succinctly: “Blast it!”

Of course, when the storm broke out in Parliament with the Opposition grilling the government over the affair, Moscow could not resist the temptation to score some propaganda points by formally protesting about the unfriendly incident.

Over a year later, a headless and badly decomposed body in a dry suit was found in Chichester harbor, and an inquest ruled it was that of Crabb.

Despite the coroner’s verdict spurious conspiracy theories about what really happened to Crabb continue to abound but the Cabinet papers show that in all probability the veteran, and less than fit, frogman prosaically drowned, taking with him the careers of quite a few top officials — and the promise of a better relationship with Russia.