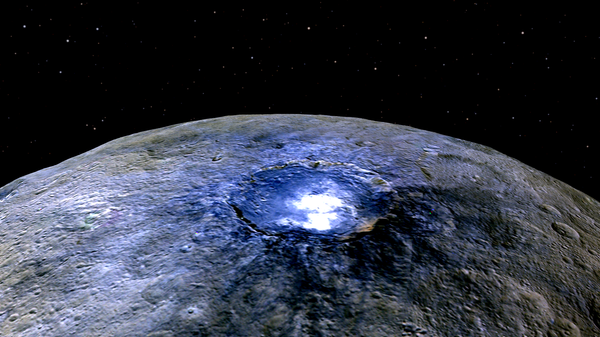

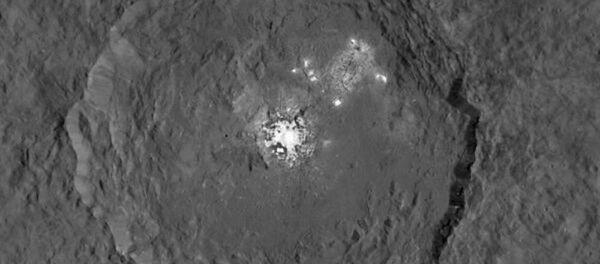

As the Dawn spacecraft approached Ceres last December, scientists eagerly awaited humanities first up-close look at a dwarf planet. Grainy images trickled in, but by March, Dawn’s cameras began to detect something unexpected: dozens of unexplainable bright spots, some as large as six miles across.

A number of theories have been put forth to explain the features. One of the more fanciful imagined the spots as the exposed segments of a vast, subterranean ocean. Others speculated that they could be signs of volcanic activity. As with any space mystery, there were, of course, those who held out hope that the spots to be related to aliens.

But a new study led by Andreas Nathues of the Max Plank Institute in Germany has conducted the most detailed surface analysis of Ceres to date, and it has zeroed in on the cause of the strange geologic features.

"The global nature of Ceres’ bright spots suggests that this world has a subsurface layer that contains briny water-ice," Nathues said, according to a NASA press release.

In other words: the truth may not be too far off from the subterranean ocean theory. The study suggests that the spots are icy patches, composed primarily of salt, hidden just beneath the surface, which became exposed after various meteor impacts, explaining why most of the spots are found inside craters.

"The simplest scenario is that the sublimation process of water ices starts after a mixture of ice and salt minerals is exposed by an impact, which penetrates the insulating dark upper crust," the researchers write.

"What we know now is Ceres is partially differentiated – it has a king of shell structure," Nathues added, according to Gizmodo.

The study has also found increased evidence for a strange haze which appears to form over two of the spots. The exact nature of that phenomenon is still unknown, but the most likely explanation is that the ice below becomes vaporized during Ceres’ daylight, and drifts back down as the body cools.

"This brightness exists only during the daytime, like haze on Earth," Nathues told Gizmodo. "This was a surprise."

Similar occurrences have been observed on comets before, but never on a rocky planetary body.

But Plank Institute’s study isn’t the only one helping to explain the Ceres. A team with the National Institute for Astrophysics in Rome published a study in Nature which found evidence that the dwarf planet contains a special class of minerals known as ammoniated phyllosilicates.

Those minerals only form in the outer reaches of the solar system, suggesting that Ceres may have formed far away before finding itself in the asteroid belt between Jupiter and Mars.

How, exactly, it would have traveled such a distance, is unknown.

But it was probably aliens.