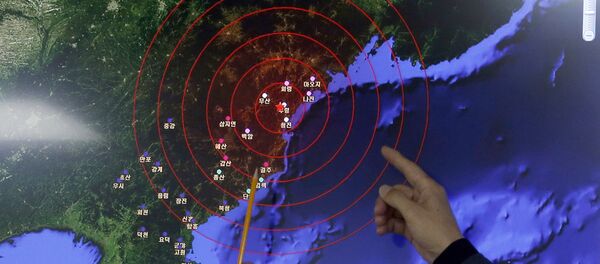

The international community has expressed outrage over North Korea’s nuclear test conducted Wednesday morning, raising the possibility of new sanctions being put in place. To sift through the facts, Loud & Clear host Brian Becker sat down with Hans Kristensen, director of the Nuclear Information Project, Paul Liem, chairman of the Korea Peace Institute, and Daniel Jasper, advocacy coordinator for Asia at the American Friends Service Committee.

While North Korea claims to have successfully tested a miniaturized hydrogen bomb, Kristensen has his doubts.

"If you look at the other nuclear weapons states in the world, it took them many, many nuclear tests and many years to develop that type of technology," he says. "So personally I’m a little doubtful that North Korea, within the span of just four tests, could have been able to somehow speed to that capability."

But even if Pyongyang’s claims are true, the United States may have no one to blame but themselves. Formerly a part of the international nuclear nonproliferation treaty, North Korea may have been forced to reconsider after former US President George W. Bush included the DPRK in his "Axis of Evil."

"I think the comment about the ‘Axis of Evil’ certainly played terribly in the DPRK, and it stands to reason that these sorts of signals that were being sent were probably being received in a hostile manner," Jasper says.

"We know that when countries are threatened with military force, be it conventional or nuclear, that they take defensive means to defend themselves," Kristensen adds. "With the announcement of the 'Axis of Evil' and the very soon thereafter invasion of Iraq, one could, if you sat in Pyongyang, have concluded that ‘we’re next.'"

But even beyond the provocations of the Bush administration, President Obama has also passed up offers in which North Korea volunteered to curb its own nuclear program.

"In January of 2015, the North Koreans did actually offer to suspend further nuclear testing if the United States and South Korea would agree to cancel the annual war games last year," Liem says.

"The US and South Korea refused to do it, but it gives you an indication of what they [North Korea] consider to be a significant, good-faith effort on the part of the United States that might move them toward these kinds of negotiations.

"I think that the position of the Obama administration actually is a Bush administration policy toward North Korea, possibly on steroids…"

As Jasper points out, these annual war games are meant as a sign of force against Pyongyang.

"These exercises have taken place for decades," he says. "They’re essentially in practice of either invading the North or in the case the North invades the South. These are preparations to strengthen the alliance…and, essentially, probably to bear a little teeth, and to show the DPRK that the US and South Korea are not going away, and this war has not ended completely, yet."

The fate of Muammar Gaddafi in Libya may have also sent North Korea a message about the dangers of surrendering nuclear weapons, once developed.

"I think the North Koreans looked at that [Libya] and they’re saying to themselves, 'what is the purpose of giving up our nuclear weapons…even if we had a peace treaty, how long would that last?'" Liem says.

As the US considers applying additional sanctions against Pyongyang, more creative solutions may be needed.

"There ample ways forward, and I think it needs to move the discussion from one of zero-sum, take-it-or-leave-it type politics, to one to find incremental steps to build mutual trust, to work toward mutual goals, and those steps exist in probably some unlikely places," Jasper says.

"There has to be some creativity in Washington."