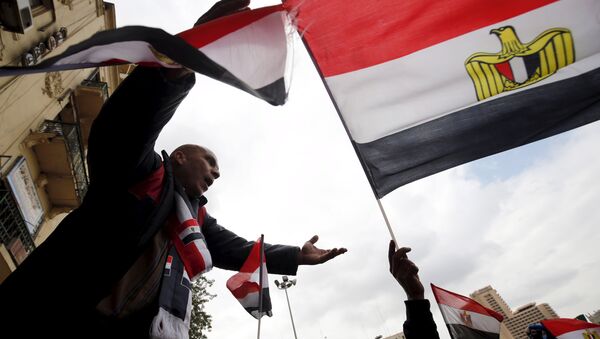

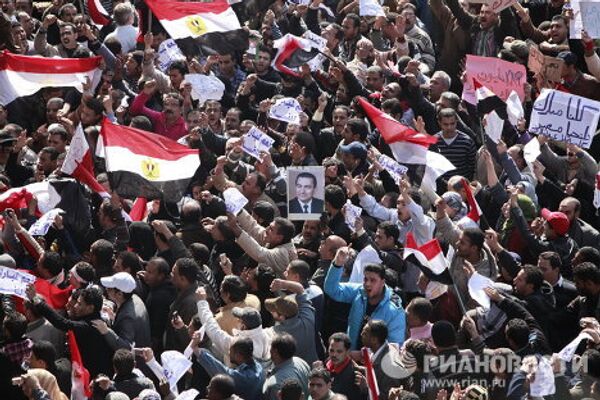

On January 25, 2011, thousands of Egyptians took to the streets of Cairo, Alexandria and other cities, inspired by the Tunisian Jasmine Revolution, which, in turn, began on December 18, 2010. Street demonstrations further grew into a national revolutionary movement which in 18 days toppled longtime President Hosni Mubarak.

The announced demands of those rallying were an end to corruption, injustice, poor economic conditions and the autocratic rule of the president.

However the recently revealed costs of the Arab Spring demonstrate the detrimental outcomes of the revolt on the economic and social development of the region.

True Cost of the Arab Spring

At the opening of the eighth edition of the Arab Strategy Forum (ASF) in Dubai in December 2015, Mohammed Al Gergawi, Chairman of the Executive Office of His Highness Sheikh Mohammed bin Rashid Al Maktoum, and Chairman of the Arab Strategy Forum released a report on the true costs of the Arab Spring revolt.

The document is based on data and information from studies by the World Bank, the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), the United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Western Asia (ESCWA), the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA), as well as the International Trade Center of the World Trade Organization, and Thomson Reuters.

For the love of Egypt #Jan25 pic.twitter.com/G4HhnK1WK0

— Lara Scandar (@LaraCScandar) 25 января 2016

As the result of the Arab Spring, by the end of February 2012, the rulers of Tunisia, Egypt, Libya, and Yemen had been forced from power; civil uprisings had erupted in Bahrain and Syria; major protests had broken out in Algeria, Iraq, Jordan, Kuwait, Morocco, and Sudan; and minor protests occurred in Mauritania, Oman, Saudi Arabia, Djibouti, Western Sahara, and Palestine.

In addition to the human cost of 1.34 million people that were killed or injured because of wars and terrorist attacks in the above countries between 2010 and 2014, the Arab Spring also registered $833.7 billion of losses.

The damage to infrastructure reached $461 billion in addition to the irreparable cost of destroyed historic and architectural sites.

The cumulative losses to sustainable GDP were estimated at $289 billion, based on GDP growth estimates and local currency exchange rates.

Stock markets and investment losses amounted to more than $35 billion, while losses to financial markets amounted to $18.3 billion and there was an estimated $16.7 billion loss in missed FDI (foreign direct investment).

The lack of stability and terrorist attacks caused a sharp decline in the number of tourists by 103.4 million between 2010 and 2014.

The number of those displaced for the same period reached more than 14.389 million people, with the refugee crisis costing somewhere in the region of $48.7 billion.

“Whether we are with or against the Arab Spring, we have to look at it in the context of history and civilization to realize that it has led to a sharp deterioration in the region, a dramatic loss in economic and growth opportunities over the past several years and destroyed the infrastructure that the region had invested decades, even centuries to build,” Gergawi then said.

The report, he added, has been compiled to raise awareness among key decision makers as well as citizens within the Arab world and elsewhere about the price the region is paying every day as a result of the chaos and instability triggered by the Arab Spring.

Chain of Events in Egypt

Back in 2011, after 18 days of protests that spilled out from Cairo’s Tahrir Square, President Hosni Mubarak handed power to military’s ruling body, the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces. Mubarak’s former prime minister, Ahmed Shafik, was tapped to lead the cabinet. The constitution was suspended and the parliament disbanded.

The military laid out a six-month timetable to draft a new constitution and hold new parliamentary and presidential elections, vowing to cede power to a newly elected civilian government within that time. In the wake of the uprising, Egypt’s well-organized Islamist groups wanted to see elections first, while the liberals and secularists preferred to write a constitution first. Ultimately the Islamists won out.

In November, Egypt began to vote in parliamentary elections, a six-week process that resulted in an overwhelming victory for Islamist parties.

In the lower house, the Muslim Brotherhood won the majority of seats, with the ultraconservative Salafis taking another quarter, putting religious groups in control of the parliament. In the upper house, Islamists took nearly 90 percent of the seats.

In June 2012, Mohamed Morsi, a Muslim Brotherhood candidate, garnered about 52 percent of the vote and became the President of Egypt.

In August, attempting to reclaim the powers of the presidency, Morsi ordered the retirement of the top Mubarak-era military leadership and nullified the military’s June declaration. He chose Gen. Abdul Fattah el-Sisi, former head of military intelligence, as his defense minister.

In November, Morsi issued a decree allowing him to take any and all actions that he deemed necessary to protect the country. The move sparked days of protests.

In July 2013, amid the wave of public discontent over the Muslim Brotherhood rule, the Egyptian army ousted President Morsi and declared a transition period in the country.

On May 26-28, 2014, an early presidential election took place in Egypt, which was won by former Defense Minister Abdel Fattah Sisi with 23.7 million votes, or 96.3 percent of the turnout.

He is currently the sixth President of Egypt.

Former President Mubarak, his sons and the majority of the country’s top officials were put on trial.

On May 9, 2015, a Cairo court sentenced Mubarak and his sons to three years in a high-security prison for corruption-related crimes.

On May 13, 2015, despite his conviction on corruption charges, Mubarak was released from custody as the court found he had already served the term during pretrial detention.

Morsi was also prosecuted on an array of criminal charges. In one trial (espionage for foreign intelligence services), he was sentenced to death.

Another trial (on charges of inciting deadly violence during the riots outside the presidential office in December 2012) ended with a 20-year prison sentence for Morsi. Another case of espionage, for Qatar, and high treason is pending. Morsi faces an additional death sentence if convicted.

In May 2015, another trial was launched. According to prosecutors, Morsi and another 24 members of the Muslim Brotherhood, which is banned in Egypt, are guilty of repeatedly insulting the judiciary in parliament, TV appearances and on social media. Morsi is charged with publicly accusing a judge of fraud.