"Ten to the power of 14 – that's roughly how many cells are contained in the body of a person who weighs 100 kilograms," Professor Boris Chichkov, lead researcher in nano-engineering at the Russian Academy of Sciences' (RAN) Institute of Laser and Information Technologies, told Rossiiskaya Gazeta (RG).

"Now lasers exist which can generate 100 million impulses a second, and with every impulse we can print 100 cells. Using those kinds of lasers a person can be printed in two hours and 47 minutes. For example, a heart could be printed in 30 seconds."

"Of course, for now that remains a scientific joke and not a real possibility. After all, a person is not just a collection of cells put into order," said Chichkov, who gave a presentation to the conference on '3D Laser BioPrinting: Past, Present and Future.'

"But I am an optimist, and I think that printed organs will enter medical practice in the next decades," Chichkov said.

Vladimir Mironov, Chief Scientific Officer at Moscow's 3D Bioprinting Solutions, told RG that kidneys are the first organs in line for bioprinting.

"First we develop it using mice, but the final aim is the creation of an industry for the bioprinting of human organs," he told the newspaper.

Around 100,000 organ transplants are carried out across the world each year, and around 25-30 percent of people who are waiting for an organ transplant die before they receive one.

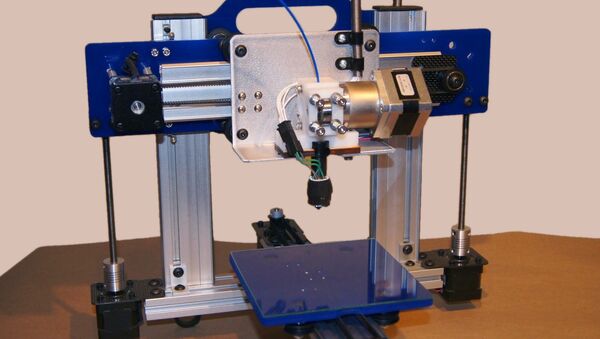

While making organs is an eventual goal for scientists, in recent years the first 3D printed prosthetics and implants have begun to be developed for patients. In 2012, an 83-year-old woman in the Netherlands received a 3D printer-created lower jaw that was printed out of titanium. She was fitted with the new jaw after she developed a chronic bone infection, and once the complex part was designed it took only a few hours to print.