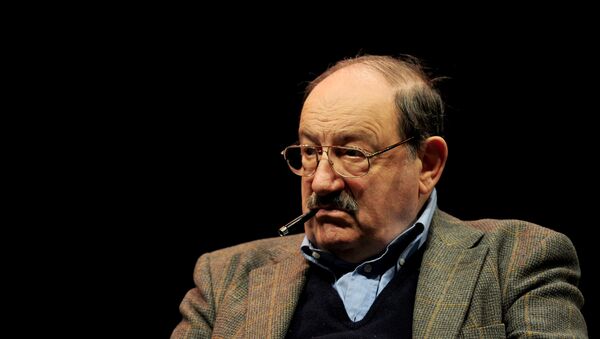

Philosopher, semiologist, master of epic erudition, medieval aesthetic specialist, fiction and non-fiction writer, Eco oscillated gleefully between the roles of "Apocalyptic and Integrated" — the title of one of his seminal books (1964). His trademark touch was a delightfully erudite synthesis of tragic optimism — as if he was the supreme erudite dreamer.

Not only he wrote numerous, priceless essays on aesthetics, linguistics and philosophy, and criticized in depth the global mediascape; he was also a best-selling fiction author, from The Name of the Rose (1980) — 14 million copies sold — to Foucault's Pendulum (1988).

With guilt — and crucifixions — out of the way, Eco was ready to bolt into the avant garde. Opera Aperta ("Open Work") comes out in 1962 — a structuralist analysis of literature based on James Joyce which became the rage on campuses from Paris to Berkeley throughout the 1960s and 1970s. The heart of the matter was how to define art. Eco proposed that the work of art contains an ambiguous message, open to infinite interpretations, as many meanings cohabit inside a single signifier. So a text is not a finished object, but "open", which the reader cannot just accept passively; he must work to re-invent it and interpret it.

Keep inspiring us, wherever you might be:(

— Marco Ciappelli (@MarcoCiappelli) 20 февраля 2016

“I love the smell of book ink in the morning.”

― #UmbertoEco#amwriting pic.twitter.com/hZ1jO5TFYy

By 1971 Eco was already teaching semiotic sciences at the faculty of Letters and Philosophy in Bologna. He saw this experimental science — launched by Roland Barthes — as more than a method; it led him to probe beyond all intersections between erudite and pop culture.

Poetry is not a matter of feelings,it is a matter of language. It's language which creates feelings. RIP #UmbertoEco pic.twitter.com/szLR3Oh1ep

— Simone Cerbolini (@SimoneCerbolini) 20 февраля 2016

Frantically imbibing pop culture, Il Professore could not but end up on TV, which he started to dissect with myriad scalps, alongside a toxic cocktail of kitsch, football, celebrity culture, advertising, fashion — and terrorism. The embryo for all this critical frenzy was contained in Apocalyptic and Integrated.

The apocalyptic media attitude reflects an elitist and nostalgic view of culture, while the integrated attitude privileges free access to cultural products, without bothering about their mode of production. And that led Eco to propose a critical view of all media, which, unfortunately, few dared to apply.

Read, and You'll Live 5,000 Years

Eco was an avid reader; at least two newspapers every morning. He loved to brag he was faithful to Hegel's idea that reading the papers was "the daily prayer of modern man". And he was also a contributor to newspapers — writing columns and essays.

As a fiction writer, he was totally post-modern. Post-modernism — endlessly discussed throughout the go-go 1980s — tried to establish critical and ironical thinking over the whole tradition of inter-textuality. But Eco was always careful to stress how the notion of post-modernism itself was muddled; post-modern in architecture did not follow Le Corbusier, in literature it did not follow the nouveau roman, it could even turn into the American school of criticism applied to narrative art, based on Borges and Garcia Marquez.

You definitely did tell stories @umbertoeco_! RIP #UmbertoEco pic.twitter.com/9m0XaQUimN

— Dunja Mijatovic (@Dunja_Mijatovic) 20 февраля 2016

Eco considered that if post-modernism in literature meant an ironic reflection over the plurality of modes of narration, the whole thing would have started with Sterne's Tristram Shandy, Cervantes and maybe Rabelais. But if the James Joyce of Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man is "modern", in Ulysses and Finnegans Wake he's definitely post-modern.

Sooner or later, Il Professore would have to be confronted with The Ultimate Wizard; Borges. He came up to the conclusion that Borges gave meaning to a tradition even more ancient; the other face of avant-garde, with on one side the ruptures of the futurists and Dada, monochrome and abstract paintings; and on the other side, surrealism.

Our hearts break yet again. You will be missed, #UmbertoEco. pic.twitter.com/r1QUnahoIt

— Barnes & Noble (@BNBuzz) 20 февраля 2016

The Name of the Rose is the ultimate post-modern novel. Eco provokes his reader at each page, proposing non-stop an enigma, an allusion, a pastiche or a mere quote amidst an arcane plot investigated by a Franciscan monk who's an avatar of Sherlock Holmes. The book can be read in at least three parallel ways; we can follow the intrigue; we can follow the debate of ideas; or we can follow the allegorical dimensions woven through a multiple game of quote upon quote, "a book made out of books". And here we have Eco as the ultimate reader of Borges.

His latest published book, Anno Zero (2015) is also a riot. It takes place in 1992 around an imaginary newsroom — throwing darts all across the juicy political, journalistic, judicial and conspiratorial history of modern Italy — from the Tangentopoli scandal to NATO's Gladio, from the P2 masonic lodge's shenanigans to the terrorism of the Brigate Rosse. No one has ever written a thriller about lousy journalism; only Il Professore could get away with it. His Rosebud: "The question is newspapers are not made to reveal but to cover up news."

It's also fitting that in the end Eco refused to be published by the Italian media colossus Mondadori-Rcs. So he started a new adventure, the Nave de Teseo ("Theseus' Vessel) publishing house. Il Professore remarked that, "Theseus is only a pretext, a name like any other. The important thing is the vessel, not Theseus." Yet another semiological prank.

A staunch reader to the end, Eco famously remarked, "who does not read, at 70 would have lived a single life. Those who read will have lived 5,000 years. Reading is retrospective immortality."

So it's also fitting there will be a posthumous Eco book, Pape Satan Aleppe, which will be out in Italy in a few days. The volume will unite the columns Eco wrote for L'Espresso magazine linked by the theme of liquid society and its symptoms; as he enounced them, "the crisis of ideology, of memory, of communities to which one belongs, the obsession with self-promotion." And what does the title mean? Eco joyfully remarked, "an evidently dantesque quote which does not mean anything, thus sufficiently ‘liquid' to characterize the confusion of our times."

What's in a Name?

After he recently received a laurea honoris causa in Communication and Media Culture in Turin, Eco caused a media storm by deriding social networks, saying they "give the right of expression to legions of imbeciles which beforehand only talked in the bar after a glass of wine, without disturbing their social environment. Now they have the same right of expression of a Nobel Prize. It's the invasion of the imbeciles."

And he was, of course, right. Everyone subjected to internet absurdities recognizes how "TV had promoted the village idiot, in relation to which the spectator felt superior. The drama of the internet is that it has promoted the village idiot to the status of bearer of truth."

Add it to "the confusion of our times", which will only become even more confused with the loss of the Great Alchemist — a joyous, riotous mix of multi-plural thinker, text freak and perennially passionate reader. What if he never got a Nobel Prize? Borges was also snubbed.

The last phrase in The Name of the Rose is "stat rosa pristina nomine, nomina nuda tenemus". "The rose that was now exists only in name, we posses only nude names." That's a variation of a verse contained in De Contemptu Mundi, by the12th century Benedictine monk Bernard of Cluny. Now only nude names echo one another under the benign shadow of the mighty Eco.

The views expressed in this article are solely those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official position of Sputnik.