"Curium is an elusive element. It is one of the heaviest-known elements, yet it does not occur naturally because all of its isotopes are radioactive and decay rapidly on a geological time scale," said Francois Tissot, lead author of the study, published in Science Advances.

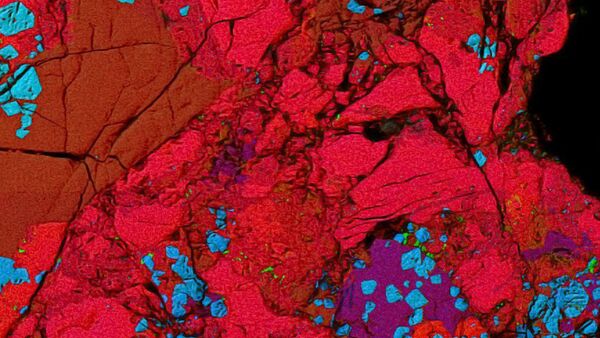

Tissot and his colleagues found evidence of curium in "Curious Marie," an unusual ceramic-like rock that was found embedded in a carbonaceous (carbon-rich) meteorite.

The rock is a refractory inclusion, which are the oldest objects known to have formed in the 4.5 billion year old solar system. The discovery proves that the element was present during the formation of the solar system.

The most stable isotope of curium, curium-247, has a half-life of about 15.6 million years and decays into an isotope of uranium (U-235).

Early studies in the 1980s found large excesses of U-235 in any meteoritic inclusions they analyzed, and concluded that curium was very abundant when the solar system formed.

A mineral or rock formed in the early solar system would be expected to contain more Cm-247 than a similar mineral or rock that formed later, after Cm-247 had decayed. If two such hypothetical minerals were compared today, scientists would find more U-235, the decay product of Cm-247, in the older mineral.

"The idea is simple enough, yet, for nearly 35 years, scientists have argued about the presence of Cm-247 in the early solar system," Tissot said.

"This is particularly important because it indicates that as successive generations of stars die and eject the elements they produced into the galaxy, the heaviest elements are produced together, while previous work had suggested that this was not the case," explained Professor Nicolas Dauphas, a coauthor of the paper.