This mindboggling technique of printing functioning human organs could save thousands of lives, but some experts still doubt that that bioprinting will even be able to create fully functioning body parts.

Others believe that 3D-printed organs will function even better than real ones.

Printed Blood Vessels

Tissue filled with blood capillaries is the latest breakthrough made in the tricky field of bioprinting.

The researchers placed living stem cells into a silicon template which served as a mold for the blood vessels.

They deliver essential nutrients to the surrounding printed environment. Eventually, the self-assembled capillaries are able to connect with the bio-printed tubes and deliver nutrients to the cells on their own, enabling these structures to function like they do in the body.

Such vascularized tissue may eventually become part of the human body and give a strong boost to the so-called “tissue engineering.”

Building Blocks

Scientists have developed a method of using stem cells in the process of 3D-printing of universal building blocks for virtually all types of human tissue.

These stem cells may eventually be used to replicate just about any part of the human body. By altering the size of these cells scientists hope to create more efficient “building blocks” to heal wounds and test new medicines.

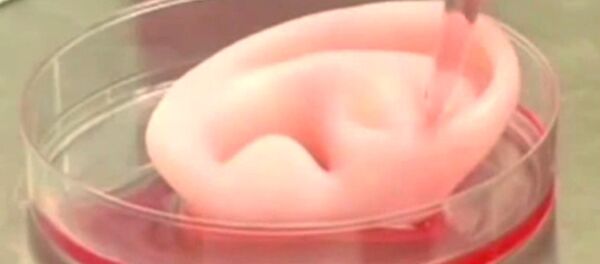

Ears, Muscles and Bones

Scientists have recently used an advanced 3-D printer to create sections of bone, muscle and cartilage that all functioned like the real thing when implanted in animals.

A team of bioengineers, led by Dr. Anthony Atala from Wake Forest School of Medicine in North Carolina, used stem cells to “grow” a human jawbone and also “printed” a full-size human ear, which looks like normal cartilage under a microscope, with blood vessels supplying the outer regions and no circulation in the inner regions (as in native cartilage).

Both were then implanted into living mice, covered with blood vessels, and eventually became part of the animal’s system.

This groundbreaking new method is not yet ready for clinical use, but its authors are sure that it won’t be long before it becomes widely applied in regenerative medicine.