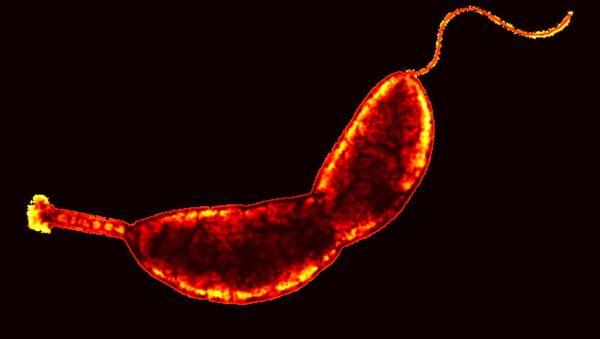

The researchers tested the memory of Caulobacter crescentus cells, a bacteria which is present in fresh water lakes and streams.

They found that when cells are exposed to a moderate concentration of salt, they are better able to survive subsequent exposure to a higher concentration of salt.

In individual cells the effect is short-lived; they only remember the salty water for 30 minutes before forgetting the experience. But when the scientists observed an entire population of the bacteria, they appeared to develop a longer, collective memory.

"If you want to understand the behavior and fate of microbial populations, it’s sometimes necessary to analyze every single cell," explained Roland Mathis, co-author of the study, published in the journal PNAS.

The scientists concluded that salt stress causes a delay in cell division, leading to the synchronization of cell cycles, which changes the sensitivity of the population.

The probability of an individual cell surviving the exposure depends on the individual bacterial cell’s position in the cell cycle at the time of the second exposure.

"If we understand this collective effect, it may improve our ability to control bacterial populations," said co-author Martin Ackermann.

Their findings can help scientists to control bacteria, which can be both harmful and beneficial. For example, they help to understand how pathogens can resist antibiotics, and could also prove helpful in controlling the performance of bacterial cultures in industrial processes or wastewater treatment plants.