"If China carries out a sustained, comprehensive effort to raise productivity, it can address its growth challenges, reduce the risks of financial crisis, and complete its transition to a consumption-driven, high-income economy with a large and affluent middle class. If it does, its annual GDP could be an estimated $5 trillion larger by 2030 than it is likely to be if policymakers continue to pursue investment-led growth," Woetzel wrote.

According to Woetzel, the level of productivity of Chinese labor is only 10-30 percent of that in developed economies, and businesses in the service sector are just 15-30 percent as productive as their counterparts in OECD countries.

"In addition to streamlining existing operations (for example, by introducing self-checkout systems in retail businesses), China has opportunities to complement its manufacturing sector with high-value-added business services in areas such as design, accounting, marketing, and logistics."

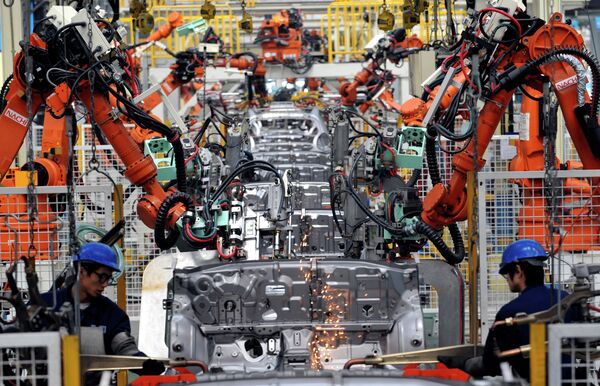

In the manufacturing sector China could increase productivity by using more robots. Though China is the world’s largest purchaser of robots, it still has only 36 robots per 10,000 workers, compared with 164 in the United States and 478 in Korea, Woetzel writes.

Woetzel believes that some of China’s biggest productivity opportunities are in industries which suffer from overcapacity, such as steel manufacturing.

"Restructuring industries like steel, by letting uncompetitive players fail and encouraging consolidation, could raise productivity dramatically without compromising the ability to meet demand," he wrote.