Daujeard and her colleagues came to this conclusion by studying the remains of an unusual group of ancient hominids, Homo rhodesiensis, a subspecies of Heidelberg people who lived in North Africa. They are the common ancestor of Neanderthals and were the modern inhabitants of Earth 120-400 million years ago. A number of paleontologists believe that these people were our direct ancestors.

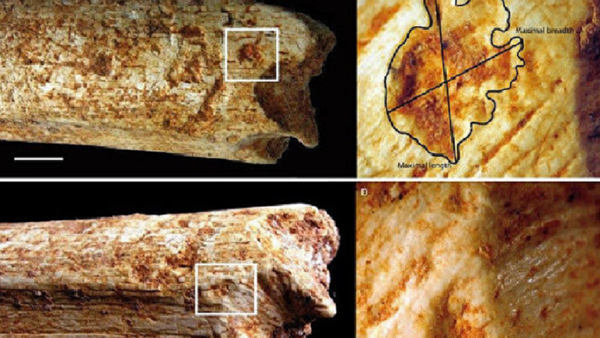

In one of the nearby excavations of Casablanca, Morocco's largest city, another group of scientists found hip bones and other remains of several Homo rhodesiensis which had marks and other scratches from an unknown source.

There were dents and holes in the bones, there were also numerous fractures and other injuries which showed that owners of these bones were eaten alive by hyenas, saber-toothed tigers or bears. Another opinion is that these bodies were ripped apart shortly after death for some other unknown reason.

As the ancient bones had been completely crushed, Daujeard and her colleagues believe that their owners fell victim to ancient hyenas who had extremely powerful jaws, according to the science journal.

Previously, scientists believed that the invention of tools and shift to an omnivorous diet brought humans to be in full-fledged competition with predators and scavengers for access to food and habitats, but there was no evidence of this before the era of Neanderthals and Cro-Magnon.

This recent discovery of traces of hyena teeth on the bones of people who lived more than 500 thousand years ago, provides some insight into the complexity of the relationship between predators and their new “competitors.”

Humans simultaneously acted as source of food, as living competitors and as predators that preyed on the former “kings” of the food chain.

The dynamic nature of this relationship, as scientists believe, was the main cause of extinction for many animal species, an example of that can be seen in the extinction of megafauna in North America.