"The ability to obtain genome-scale data from ancient bones is a new technology that’s only been around for the last five or six years," explained David Reich of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute (HHMI), leader of the study published in the journal Nature on Monday.

"It’s a new scientific instrument that makes it possible to look at things that have not been looked at before."

Prior to this study, there were only four samples of prehistoric European modern humans 45,000 to 7,000 years old for which genomic data were available, HHMI explained in a press release.

The scientist were able to obtain more samples by using about 1.2 million 52-base-pair DNA sequences to target specific segments of DNA they were interested in finding in the bones.

They washed the ancient DNA over the 1.2 million probe sequences, and then sequenced the ancient DNA that was captured by the probes.

"Trying to represent this vast period of European history with just four samples is like trying to summarize a movie with four still images. With 51 samples, everything changes; we can follow the narrative arc; we get a vivid sense of the dynamic changes over time," Reich explained.

"And what we see is a population history that is no less complicated than that in the last 7,000 years, with multiple episodes of population replacement and immigration on a vast and dramatic scale, at a time when the climate was changing dramatically."

Before that, 37,000 years ago, all Europeans come from a single founding population that persisted through the Ice Age.

Around 33,000 years ago this branch was displaced in most parts of Europe but it seems that around 19,000 years ago, after the continental ice began to retreat, a related population re-expanded across Europe, probably from southwest Europe, for example modern-day Spain.

The first group of European humans was again displaced in a second wave of migration, this time from the east, for example modern-day Turkey and Greece.

"We see very different genetics spreading across Europe that displaces the people from the southwest who were there before. These people persisted for many thousands of years until the arrival of farming," Reich explained.

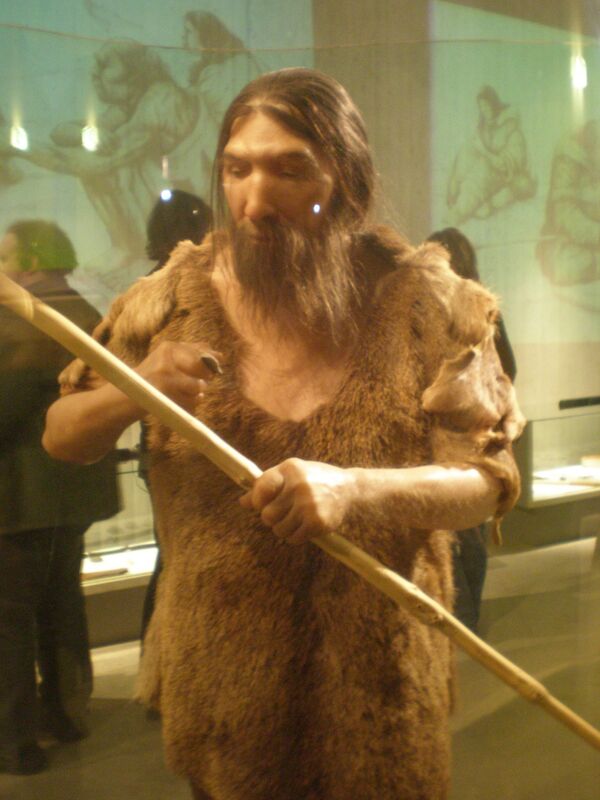

"Neanderthal DNA is slightly toxic to modern humans," Reich explained.

While the ancient human populations carried three to six percent of Neanderthal DNA, today's humans only have about two percent.