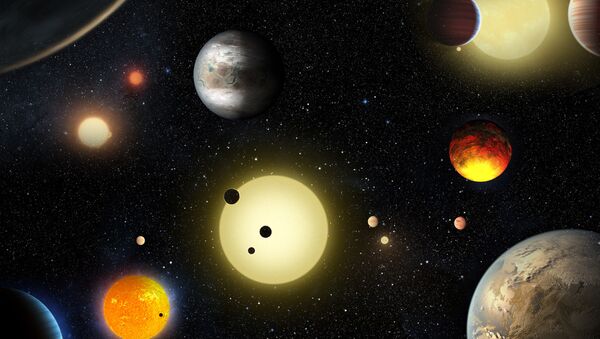

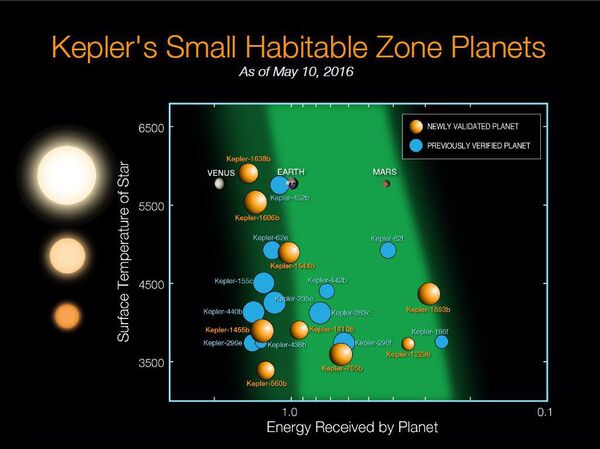

Based on their size, nearly 550 of them could be rocky planets like Earth, and nine of these orbit in their sun's habitable zone, the distance from a star where orbiting planets can have surface temperatures that allow liquid water to pool.

With the addition of these nine, 21 exoplanets are now known to inhabit this "Goldilocks Zone" around their respective stars.

"They say not to count our chickens before they're hatched, but that's exactly what these results allow us to do based on probabilities that each egg (candidate) will hatch into a chick (bona fide planet)," said Natalie Batalha, a Kepler mission scientist at NASA's Ames Research Center.

"Before the Kepler space telescope launched, we did not know whether exoplanets were rare or common in the galaxy. Thanks to Kepler and the research community, we now know there could be more planets than stars,” said Paul Hertz, the agency's Astrophysics Division director.

The Kepler telescope, named after the Renaissance astronomer Johannes Kepler, was launched in March 2009. It works by measuring the brightness of stars; whenever a planet passes in front of its parent star as viewed from the spacecraft, a tiny pulse or beat is produced.