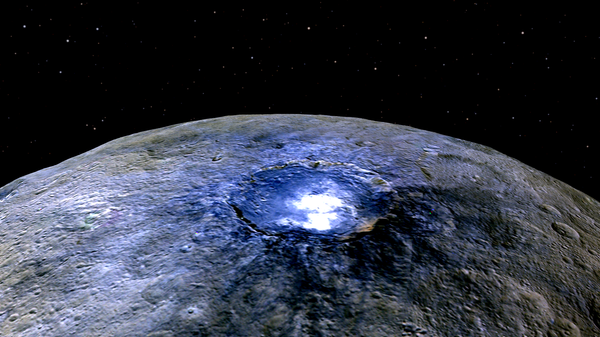

An intriguing bright spot on the 945-kilometer-diameter Ceres, the largest asteroid between the orbits of Mars and Jupiter, was first imaged by the Hubble orbital telescope at the end of 20th century. Due to the planet's small size and the limits of available technology, the images of the planet were at a resolution of about 30km per pixel, too small to discern usable details. The brightness remained a single large white blob.

The nature of the two spots is hotly debated by astronomers, with two prominent versions suggesting either ice or salt. Ceres is known to possess large amounts of frozen water beneath its surface, and ice is thought to be a natural explanation. Chris Russell, of the University of California at Los Angeles, has studied the bright spots and initially supported this theory, but later admitted that the object's albedo, or reflectivity factor, indicates that the material is likely salt.

In 2015, Paolo Molaro, of the Trieste Astronomical Observatory in Italy, studied Ceres using a High Accuracy Radial velocity Planet Searcher (HARPS), located at La Silla Observatory, in the Atacama desert in Chile. While examining the data, Trieste scientists discovered that the bright spots change their shape consistently over set time periods. These periods correlate with time during which the bright spots can be seen from Earth.

As astronomers seek to explain this newly-discovered phenomena, a hypothesis has been proposed that the Occator crater is covered with a volatile substance that reflects sunlight while solid, but then evaporates, losing its reflectivity. This theoretical substance could be either water ice, or clathrates hydrates, a solid form of natural gas, bound by water molecules.

This theory is supplemented by Russell's discovery of a haze that sporadically appears over the bright spots.

If the volatile-substance theory is confirmed, it would indicate that Ceres is volcanically active. As the dwarf planet is already known to be rich in water, internal geothermal activity could provide the necessary elements and energy to support microbial life. The occasional evaporating haze could also indicate an atmosphere, contained within a local surface region.

The Molaro team awaits new imagery from Dawn, which is providing additional information and precise measurements.