"It was the first planet to form, so it gives you that very first step [of] what happened after the sun formed that allowed the planets to form because that’s really the history of not only our system but us here at Earth."

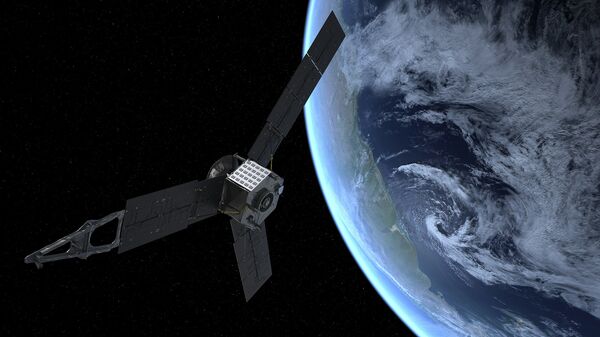

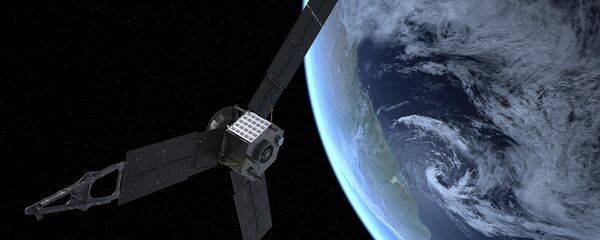

On July 4, rockets on Juno — a dish-like spacecraft with three solar panel wings the size of a basketball court — will burn for 35 minutes, slowing the speeding satellite enough to be captured by Jupiter’s gravity and placed into orbit over the planet’s poles, Bolton noted.

Juno will orbit for two years, sending reams of images that will be available on NASA websites, and a flood of data from sensors that are heavily shielded from a violent radiation storm that is unique in its intensity to the solar system’s largest planet.

When the mission is complete, Juno will plunge into Jupiter’s atmosphere and burn up, thereby avoiding the remote possibility that it could hit one of the planet’s moons, Europa, and contaminate primitive forms of life that may exist in a massive ocean that lies beneath that moon’s surface.