On May 2, 1941, less than two months ahead of the beginning of Nazi Germany's Operation Barbarossa, Richard Sorge, one of the greatest Soviet spies, informed the Kremlin that Adolf Hitler was determined to invade the USSR.

"I talked to German ambassador Ott [Eugen Ott, German ambassador to Japan] and a marine attaché about the relationship between Germany and the USSR. Ott stated that Hitler is determined to defeat the USSR and get his hands on the European part of the Soviet Union as a grain and resource base for Germany's control over the whole Europe… The possibility of a sudden war is especially high, since Hitler and his generals are confident that the war with the USSR will be no hindrance to [Germany's] war against Great Britain," Sorge wrote, as quoted by Russian historian and analyst Professor Anatoly Koshkin in his article for Regnum.

"German generals estimate that the Red Army's military capabilities are so low, that the Red Army will be destroyed within a few weeks. They believe that [the USSR's] defense at the Soviet-German border is extremely weak," the Soviet intelligence agent added.

Being discharged from the army in 1918, Sorge joined the German Communist Party a year later. At the time the future espionage mastermind studied political science at the University of Hamburg.

Since the connections between German and Soviet Communists were close, in 1924 Sorge got in touch with four Comintern (the Communist International) delegates from the USSR who suggested him moving to Moscow, American historian Gordon W. Prange narrated in his book "Target Tokyo: The Story of the Sorge Spy Ring." Since then Sorge's career as a secret agent began.

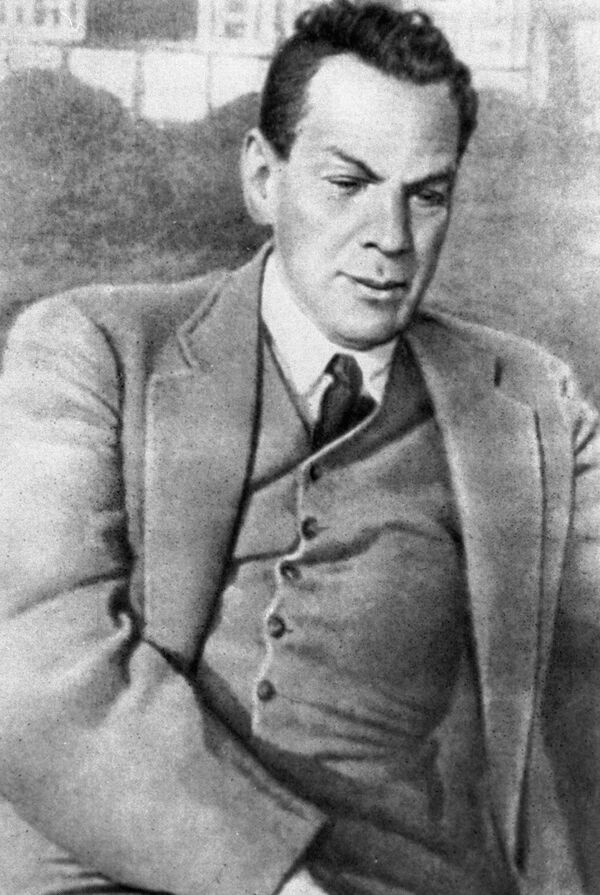

In the mid-1930s, Richard Sorge, a reputable Frankfurter Zeitung's journalist and Nazi Party member, was sent to Tokyo, Japan, as Nazi Germany's foreign correspondent. Needless to say, it was a splendid cover for the Soviet spy. In Japan Sorge penetrated the German embassy and gained access to priceless confidential data on Berlin and Tokyo's political and military plans.

On May 30 the Soviet intelligence officer warned: "Berlin has informed Ott that the German invasion of the USSR will start in the second half of June [1941]. Ott is 95 percent sure that the war will start [soon]."

On June 20, just two days before the beginning of the Nazi invasion of the Soviet Union, the Kremlin received the final warning from Sorge: "The German ambassador in Tokyo told me that the war between Germany and the USSR is inevitable…"

According to the Russian online newspaper Vzglyad, the situation was not as easy as it seems today.

Sorge was not the only intelligence agent who sent warning signals to the Kremlin.

"With all due respect to the heroism of our intelligence forces, it should be noted that, if the reports of agents were to be arranged in chronological order, the following picture would emerge: In March 1941, agents 'Starshina' and 'Korsikanets' reported that the attack would begin around May 1. A report from April 2 suggested that the war would begin on April 15. And a report from April 30 said it would start 'any day now'. A report from May 9 predicted 'May 20 or June'. Finally, a report from June 16 said: 'the blow can be expected at any time'," the newspaper revealed, adding that Sorge alone named at least seven different dates for the beginning of the war.

In light of this it was hard to forecast the exact date of the invasion, Vzglyad noted.

However, Sorge contributed greatly to the USSR's military success in the Second World War.

In summer 1941, the information about Japan's military plans was of ultimate importance to the Soviet government, Koshkin stresses. If Japan joined its ally, Nazi Germany, and kicked off an advance on the USSR's Far East following Hitler's attack in the West, it would severely deteriorate the situation.

Koshkin narrates that Joseph Stalin decided to seize this unique opportunity: after the information was rechecked, the Soviet leadership transferred part of its Far Eastern and Siberian divisions to Moscow. It helped to prevent the Russian capital's fall and postponed Japan's invasion.

At the same time it marked the beginning of the end of Hitler's ambitious Barbarossa campaign. And Soviet intelligence officer Richard Sorge deserved a lot of credit for this success.