The X-rays — which were produced when the monster black hole obliterated the star — reached Earth in 2011 and were picked up by NASA's Swift satellite. Within days of the observation scientists concluded that the x-rays that had been observed represented the "tidal disruption" of a star and the "sudden flare up of a previously inactive black hole."

By applying new research method to the archived data scientists have now been able, for the first time, to map the flow of gas near a newly awakened black hole, giving insight into the dramatic events that can occur around the elusive "star killer."

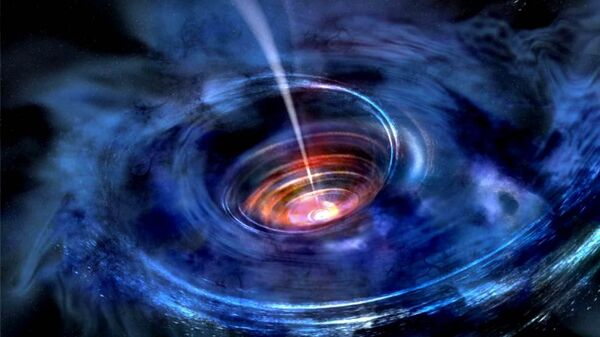

These gas flows are known as accretion disks, and occur when stellar debris falling towards a black hole collects and forms a rotating structure.

Black holes are one of the most important areas of study in modern astrophysics. Despite their name, black holes are far from "empty," they contain a incomprehensibly large amount of matter, condensed to extreme levels. They are referred to as black holes, as according to classic physics the pull of their gravitational force is so great that not even light, or any electromagnetic radiation, can escape them.

The only method of studying black holes is therefore through observations of radiation emitted close to their inferred presence.

" so-called X-ray reverberation, in which the energy is seen bouncing around as it prepares to be eaten." Wow. https://t.co/ey567AXeJH

— Jerome Ludwig (@jeromeludwig) June 22, 2016

X-ray reverberation mapping had previously been used to observe stable accretion disks around black holes. However, the study of stable accretion disks doesn't give as great an insight into the workings of the stellar structures as the study of these tidal disruptions.

NASA Goddard astronomer Erin Kara, decided to apply the X-ray reverberation method to the previously collected data after a conversation with a colleague over lunch, and after applying the method could for the first time view deep into the structure of the inner accretion disk around a normally dormant black hole.

This new method allows for a greater population of black holes to be studied.

Goddard team member Chris Reynolds, said:

"If we only look at active black holes, we might be getting a strongly biased sample… It could be that these black holes all fit within some narrow range of spins and masses. So it's important to study the entire population to make sure we're not biased."

The mapping method itself is similar to the way sonar is used to map sea floors — by observing the X-rays and echoes emitted as a star is sucked into a black hole, astronomers can map the regions close to the structure.