These genes can’t bring a person back to life, but this discovery has serious implications for forensics and organ donor recipients.

“For us, this experiment was a chance to satisfy our scientific curiosity and find out what happens when we die. The main conclusion of our study – it showed that we can learn a lot about how life works, studying her death,” said Peter Noble from the University of Washington in Seattle.

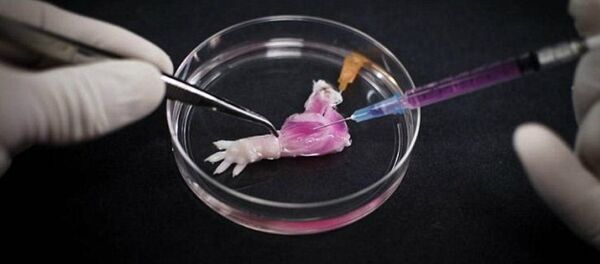

Studying the cells of mice and fish-zebras, killed by lethal doses of poison, Noble and his colleagues determined that there exist several such geneses in the body of humans and animals that start functioning only after their owner is dead.

Also, genes that construct the embryo were also found to activate after death, probably because the cellular conditions of the newly dead organisms are comparable to those of embryos.

Some of the reactivated genes promoted cancer, which explains why some donor recipients develop this deadly disease.

Importantly, these genes and their performance, which the scientists describe as tanatoterapiya, can be used to determine the exact time of someone’s death and determine whether his or her organs are suitable for transplantation.

Monitoring the activity of genes in dying cells will give scientists a clue to how ”life works.”