The quarrel over the disputed Spratly Islands is intensifying. Last week, anonymous Western diplomats and military officials told Reuters that intelligence had confirmed that Hanoi was moving mobile missile launchers from mainland Vietnam to five separate facilities in the Spratly archipelago. According to experts, the Chinese facilities in neighboring islands are within the missiles' range.

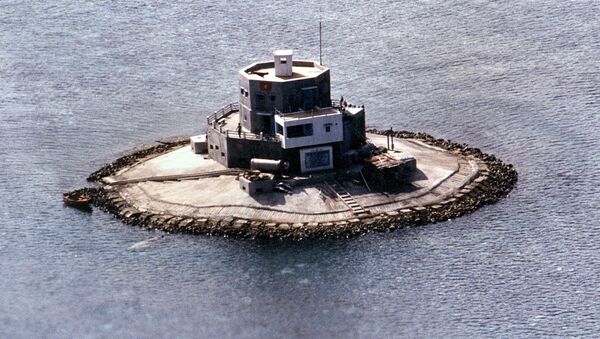

The Spratly archipelago consists of over a hundred small islets, their total area less than five square kilometers, with the largest, Taiping Island (also known as Itu Aba and several other names), having an area of about 46 hectares. The archipelago sprawls over a total area of over 400,000 square kilometers.

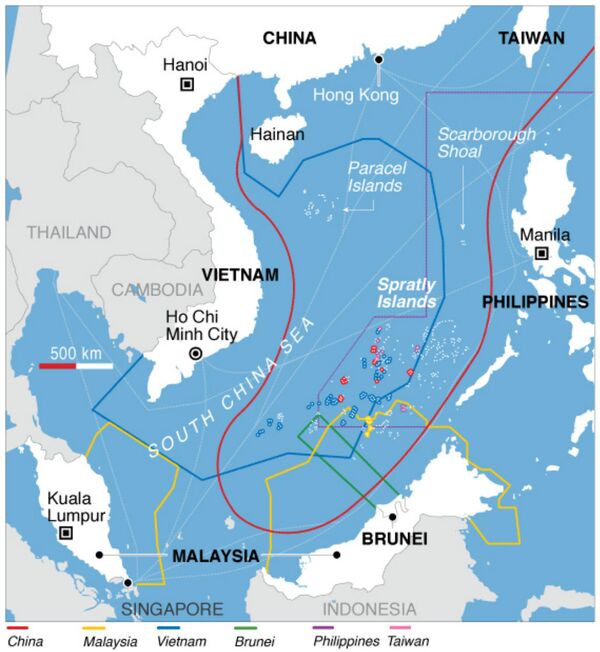

"This jumble," writes PolitRussia contributor Boris Stepnov, "is simultaneously claimed by Vietnam, the Philippines, China, Taiwan, Malaysia and Brunei; and this despite the fact that most of the 'islands' can only be conditionally called as such."

Discussing Hanoi's decision to place missile launchers in the area, the journalist suggested that "this demarche is the largest Vietnam has made in this area in recent years."

"It was obviously caused by the Hague Court of Arbitration's July 12 decision on the illegality of China's claim to the Spratly archipelago in favor of the Philippines," he added.

Commenting on the missiles' deployment for the Russian business newspaper Kommersant, Institute for Far Eastern Studies researcher Vasily Kashin suggested that the measure actually means very little in the conventional military sense.

"In real combat, the survival of these systems would depend on their ability to be quickly moved to avoid return fire." Accordingly, "the aim, when placing them on 100x100 meter islands," where there is literally no room for maneuvering, "can only be demonstrative," Kashin said.

As expected, the Chinese Foreign Ministry responded to the deployment by saying that Beijing "resolutely opposes [Vietnam] occupying parts of China's Spratly Islands and reefs…[and] carrying out illegal construction and military deployments."

However, Stepnov suggested that it's worth noting, for fairness' sake, "that China in its section of the Spratlys is building dual-use facilities that can be used for military purposes. Moreover, since 2013, China has been confidently carrying out engineering and the construction activities in the archipelago, building artificial islands, deepening waterways, and creating new berthing facilities…China, naturally, has said that the infrastructure has peaceful purposes – meant for search and rescue operations, as well as scientific research in navigation. Foreign analysts, however, have suggested that its main purpose is to strengthen China's military potential in the region. Specifically, China is now completing the construction of an airstrip on one of its seven artificial islands."

Thankfully, the analyst noted, a hot war between China and Vietnam remains unlikely, for the moment. "If China puts too much pressure on Vietnam, the latter will likely run to the US for protection, which is clearly not something China wants. At the same time, the two countries have experience of cooperation – for example, via the recent joint anti-terrorism exercises."

"The problem, as usual, has to do with oil," Stepnov wrote. "According to the US Department of Energy, the archipelago contains the equivalent of some 5.4 billion barrels of oil, and over 55 trillion cubic meters of natural gas. What's more, the region has a value as a fishery zone."

"And that's not the only problem," the journalist noted. "take a look at the size of China's claims: They are a bit immodest, aren't they?"

"As we can see, the disputed archipelago is China's main sea route for access to Europe, Africa and the Middle East. About 60% of the country's total trade, and nearly 80% of its imports of hydrocarbons, pass through the area. China simply cannot afford to lose control over this territory; otherwise whoever does come to control it will be able to block most of China's maritime transport. Therefore, China is ready to buy the archipelago out from other claimants, and as can be guessed, is not enthusiastic about allowing the United States to serve as a 'third party' in the negotiations."

Beijing has decisively rejected the Hague Tribunal's ruling in their spat with the Philippines, and vowed to defend China's claims to sovereignty over the area. "As for Vietnam, it's already been mentioned that their moves are a symbolic action. But here the US is a far more serious player, which has had a nearly constant presence in the disputed area recently."

Last month, the US Navy deployed destroyers including the USS Spruance, the USS Momsen, the USS Stethem, and the USS Ronald Reagan carrier strikes group to the South China Sea, with US Pacific Fleet spokesman Lt. Clint Ramsden emphasizing that "US Navy forces have flown, sailed, and operated in this region for decades and will continue to do so."

MT @eslavin_stripes: @Gipper_76 back at Yokosuka, Japan after a 7-week trip, mostly in the South China Sea. pic.twitter.com/ez5ELRzjRW

— U.S. Navy (@USNavy) 26 июля 2016 г.

Against this massive force, the deployment of the Vietnamese missile launchers looks like "a mere trifle," Stepnov suggested.

At the same time, the journalist pointed out, "Hanoi is also steadily moving closer to Moscow and the countries of the Eurasian Economic Union, even while Washington attempts to attach it to its Trans-Pacific Partnership trade agreement."

As far as the dispute over the South China Sea is concerned, Stepnov noted that Russia's position is very simple, and fair.

Last month, Russian Foreign Ministry spokeswoman Maria Zakharova noted that "Russia is not a party in territorial disputes in the South China Sea, and will not be dragged into them. We do not take any side as a matter of principle. We firmly believe that involvement of third parties in these disputes will only fan tensions in the region. Consultations and talks on territorial disputes in this region should be held directly by the parties involved in the format that they themselves deem appropriate."

There's a clear logic to the Foreign Ministry's position, the journalist suggested. "Given that so many countries have territorial claims, the solution is political, not arbitration-based. States should negotiate with one another, rather than delegating to organizations which not all parties recognize." This is what occurred in the case of the Hague's arbitration effort, which China rejected long before they ever made their ruling.

Ultimately, while Moscow may not have the diplomatic or political capital necessary to help resolve the conflict between all parties to the Spratly dispute, at least as far as Beijing and Hanoi are concerned, Russia's many decades of friendly relations with the two countries may be just what China and Vietnam need in an impartial go-between. Who else if not Moscow can the two countries turn to if they are seeking a fair mediator – one who has no interest in the dispute except to seeing its peaceful resolution?