On Tuesday, Japanese media reported that the Japanese government is eager to engage in major economic cooperation with Russia, even if the two countries remain unable to reach progress in resolving the decades-long dispute over the South Kuril Islands, (known in Japan as the Northern Territories).

Citing multiple diplomatic sources, Kyodo News Agency explained that the government's new position constitutes a major departure from Tokyo's long-held policy, which held that Japan would only offer Russia economic cooperation projects if the territorial dispute over the Kurils was first resolved. Now, Japanese leaders apparently seem to hope, economic relations "will help build a relationship of mutual trust which, in turn, may lead to progress on negotiations over the territorial issue."

Russia and Japan never signed a permanent peace treaty after the conclusion of the Second World War, in part due to pressure on Tokyo from Washington, and in part to a disagreement between Moscow and Tokyo over four islands – the Southern Kurils, which transferred hands to the Soviet Union at the close of the war.

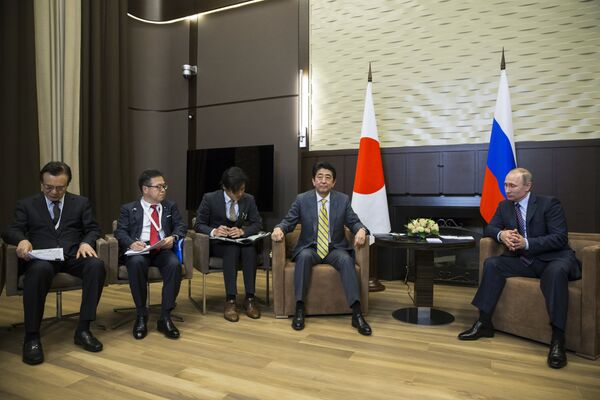

Now, months after the meeting between President Vladimir Putin and Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe in Sochi in May, Tokyo appears to have formulated a new approach to bilateral relations. At that meeting, the leaders agreed to the resumption of negotiations on signing a peace treaty, and Abe announced that he was confident that a solution to the territorial issue was sure to be found.

At the same time, Japanese media have reported that the government remains fearful that a shift in policy may actually delay the settlement of the territorial issue. For this reason, some Russian commentators, including Japan expert Andrei Fesyun, believe that Tokyo's statements may only be declarative in nature – intended to revive Russian-Japanese dialogue on the eve of the new meeting between Putin and Abe on September 2.

At the same time, Fesyun admitted that in a situation where the global geopolitical balance is shifting away from US-dominated unipolarity, Tokyo's apparent reevaluation of the idea of cooperating with Russia may be genuine.

Speaking to Sputnik Japan, the analyst emphasized that "Tokyo doesn't have any real plans to retreat from its position on the territorial dispute."

"On the other hand, they are facing continued pressure from China, both economically and militarily. At the same time, they can't help but observe the weakening role of the US [in the region], and its attempts, which have proven too weak, to 'contain' Beijing in areas around China's territorial waters."

Effectively, the analyst suggested, this kind of rhetoric by Tokyo's partners in Washington "is forcing Japan to look around – if not for a search for new partners, then at least for countries on which it could bank on without expecting something unexpected and negative. And in this regard…Russia could serve as a very reliable partner for Japan."

First and foremost as an economic partner, Fesyun clarified. Russia, he noted, does not have any aggressive plans toward Japan or any of its neighbors. Accordingly, in the analyst's view, while Japan will never abandon its position on the territorial issue, it is expected that it will become less of a centerpiece to future cooperation. And then, major economic projects would no longer be held back, to the benefit of both countries.

"Economic relations between our countries depend on the flagships of Japanese business. And they, up to this point, have been in no hurry to make any overarching, comprehensive decisions. This has not prevented the attempts of small and medium-sized enterprises from entering the Russian market, as evidenced recently by the major project on gas processing on Sakhalin, or the creation of a tourist and spa complex on the island… But until now, [cooperation] has not been of the scale that we would like to see."

For his part, Valery Kistanov, the director of the Center for Japanese Studies at the Institute of Far East Studies at the Russian Academy of Sciences, said that he considered this shift in Tokyo's policy is an attempt to resolve the territorial dispute from another angle.

Speaking to Russia's Svobodnaya Pressa, Kistanov recalled that for many, many years, Japanese policy toward Russia "has been about one thing: linking politics and economics. Earlier, Tokyo placed politics first. The Japanese announced that without a solution to the territorial issue, there could be no economic cooperation with Russia. They even had a special term for this policy position, which translates from Japanese as 'the inseparability of politics and economics'."

"This approach prevailed in Japan in the first half of the 1990s, after the Soviet Union collapsed and Russia was lying in ruins. Tokyo considered at the time that Moscow would be willing to do anything for the sake of foreign investment, and Boris Yeltsin's policy in other areas gave them grounds to have such expectations. However, this approach didn't work, and Yeltsin ultimately did not agree to an exchange."

Accordingly, Kistanov suggested, Tokyo has come up with a new approach, one which can be summed up as follows: "Here is economic cooperation. We hope that you will appreciate it, understand what benefits it will bring, and out of gratitude, will agree to concessions."

Pointing out that even members of Abe's own government have voiced their skepticism to this approach, the analyst noted that it seems that Prime Minister Abe has decided that he has no other option: "everything else which was possible has already been tried."

At the same time, Kistanov explained that many aspects of Russian-Japanese cooperation would be of benefit to Japan itself. "It's worth recalling that the first item on the agenda for cooperation [in Abe's 8 point roadmap] is in the field of energy. In this area, Japan is interested in cooperating without any additional strings attached: Tokyo desperately needs Russian energy resources…"

Japan has also offered investment and aid in other areas, from agriculture to city infrastructure. But in all these areas, Kistanov noted that there will be a host of serious obstacles to overcome, from bureaucracy, taxes and customs legislation to fears by local business that they will lose out to big Japanese capital if the projects go ahead.

Ultimately, the analyst suggested, the dispute over the Kurils will not be resolved without taking local realities, into consideration, including the attitudes of the local population.

"In the 1990s, when Moscow lived for itself, and basically abandoned the Far East, the Kurils suffered a deep decline. Residents started to leave en masse. Those who stayed behind began receiving humanitarian aid from Japan, and ended up doing so from 1992 to 2009. At one time, the people on the island really did seem to come to the conclusion that Moscow had forgotten about them, and maybe it would be better to be with Japan. Incidentally, the aid provided by Japan was very basic, consisting of things like medicine and mobile generators."

"Eventually, these sentiments evaporated; the economic situation in Russia stabilized, and Moscow got around to thinking about the Kurils and their problems. In 2005 the government adopted a program on the islands' development."

Therefore, Kistanov noted, "as far as public opinion in the Far East is concerned, Tokyo will never be able to convince the region that the Kurils must be given away." But neither does that mean that they are opposed to increased economic cooperation with Japan, or even political partnership with Tokyo. The latter, naturally, would require Japan to exit from the anti-Russian coalition led by the United States.