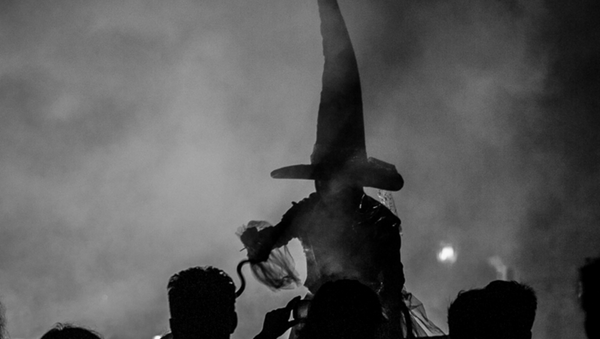

Those accused of being witches are reportedly kept in mud huts in unsanitary conditions. Some have been imprisoned for decades, like Sano Kojo, now 70, who has been detained since 1981 for allegedly pressing on a cousin's chest until he died. In Ghana, tough-talking women and those that do not automatically accept the orders of men are at risk of being accused of witchcraft.

Attempts to close witch camps in Ghana have been made repeatedly, but freedom is not always the better option. Those accused of witchcraft are often not accepted in a community and are at risk of sexual abuse and other forms of violence.

In August Jon Benjamin, British High Commissioner to Ghana, called for the closure of all witch camps in Ghana.

"Personally, I believe in the 21st century, it's time to say there is no such thing as a witch and to decry the practice of using such a term to dehumanize vulnerable women," he said.

Benjamin suggested that the practice is a form of human rights abuse and pledged Britain's support in fighting gender violence. "For the UK, tackling violence against women and girls is a high priority because it presents a major obstacle of ending gender inequality," he stated.

In 2014, the government of Ghana closed down a camp at Bonyasi, a community in Central Gonja District in the northern part of the country. The Ghanaian Ministry of Gender, Children and Social Protection has recently disbanded several witch camps but prejudice and ignorance remain in the central African country.