"Everything that we're doing right now is kind of off the cuff," Air Combat Command (ACC) spokesman Benjamin Newell told Military.com. "You have smart people out there with some good experience; however the more time we have to train for these [missions] the better [the] effect that we can bring."

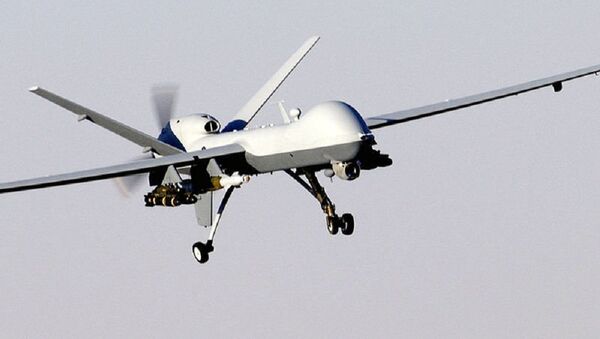

The MQ-1 Predator and MQ-9 Reaper, drones that can carry missiles, jointly represent the largest major weapons system the Air Force has, according to Military.com. The service plans to transition from Predators to the larger Reapers over the next two years. It also plans to bring on more operators for them, and a more methodical system.

The new training and new drone installations are part of a strategic effort, a drone operations chief at ACC told Military.com. It was announced late last year that, for the first time since 1957, enlisted men would be able to pilot unarmed drones and perhaps armed drones as well. Previously, enlisted men had been restricted to crew roles.

Armed drone pilots fly around 1,000 hours annually, according to the Air Force, compared to the average fighter pilot’s 250 hours, leading to stress, fatigue and overwork — and to the service losing pilots faster than they can be recruited. In 2014, 240 veteran pilots left the field, while only 180 new pilots were trained.

Currently, training needs are so intense that, "we're doing majority of our training during combat operations," the chief said. This does not interfere with combat operations, he said, but is done as time becomes available. Creating new drone bases will provide for "additional airspace, facilities and equipment," he said.

In September, the Air Force announced eight potential host bases for new drone units, and is now doing studies at four more bases around the country to house drones. Several other locations, including bases in Arizona, Georgia, Idaho, Nebraska and South Carolina, would house crews but not the aircraft themselves.

Determining the best bases will include factoring airspace, the ability to fly aircraft in particular locations, weather, and space for maintenance crews to work, the chief said. Distributing new airmen will help create more leadership positions and more opportunities for advancement, he asserted.

"Unlike weapons systems where you take 10 to 15 years on how to best methodically work through it, this has been a… continual surge to add just one more, add just one more, and we didn't really have the opportunity to do it right," another lieutenant colonel told Military.com recently.

"It's what got us to this point today where we're at this stress in the career field, and trying to build it for a sustainable, long-term operation instead of 15 years of wartime surge."

In August, it was announced that drone pilots would be eligible for an annual $35,000 retention bonus, $10,000 more than the current incentive, by Oct. 1. The higher bonus is available to eligible airmen operating drones who renew their active-duty service commitment for a five-year period.