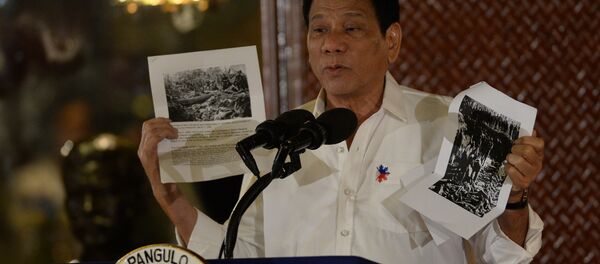

The conflict between Manila and Washington is intensifying. In a series of speeches earlier this week, President Rodrigo Duterte said that he was ready to "break up with America" and to realign his foreign policy toward other powers because the US "has failed us."

The president also warned that if Washington refuses to sell arms to his country, he could easily turn to Russia and China.

"If you don't want to sell arms, I'll go to Russia." Duterte said. "I sent the generals to Russia and Russia said 'do not worry, we have everything you need, we'll give it to you'…As for China, they said 'just come over and sign and everything will be delivered'."

Moscow seems to have been taken aback by Duterte's unexpected overture. On Monday, commenting on Manila's initiative to improve relations, Kremlin spokesman Dmitri Peskov said only that "traditionally, Russia has sought friendly, mutually beneficial and constructive relations with Washington, Beijing and Manila – in all directions."

Geopolitical analyst and Svobodnaya Pressa columnist Sergei Aksenov was more blunt, suggesting that Duterte's proposal is fully in line with Moscow's strategy of promoting global multipolarity.

"The exit of Washington's strategic ally from its absolute influence is consistent with the interests of our country," Aksenov explained. "At the same time, it's important to note that Duterte is not rushing from one ally to another, but looks to maintain a multi-vector policy which is first and foremost in the interests of his own country."

Essentially, the analyst suggested, the president of the Philippines is engaged in bringing a formal end to the former US colony's present status, including in the area of military cooperation. Earlier this week, the president pledged to end joint US-Philippines military exercises. Before that, he warned that he might ask that US to pull its troops out of the country altogether.

The reasons for Washington's pussyfooting are obvious, according to Aksenov: "The loss of the Philippines would create problems for US dominance in the region, strengthening the position of China, which Washington continues to try to restrain by igniting a conflict between Manila and Beijing over disputed islands in the South China Sea." But "now, in connection with Duterte's new course, artificial tensions may disappear, replaced by political pragmatism."

What's more, Washington also has economic reasons for concern – including threats to its plans for the Trans-Pacific Partnership Agreement (TTP), which would ensure US economic supremacy in the region. In the case of the Philippines, Manila's previous policy of supporting the agreement may change, the analyst noted.

"It's also worth noting that Washington will have a difficult time forcing Duterte to change his plans," Aksenov stressed, pointing to the president's 91% 'trust' rating, and 76% approval three months into his presidency, which analysts have suggested is due to his tough approach to the war against narcotics.

Accordingly, in a situation where Duterte is telling Brussels to go to "purgatory," and President Obama to "go to hell," Russia, Aksenov says, had best take advantage of this foreign policy u-turn.

Furthermore, if Manila seeks to assert itself in disputes in the South China Sea, it may turn to Russia for air defense systems, including the Buk and Tor medium and short-range SAM systems.

"As far as more modern systems, including the Vityaz and Morphei, they have yet to be introduced in our own military, so the Philippines is unlikely to get them," Kornev explained. "More serious systems – like the S-300, won't be delivered, because their production has been stopped; the S-400 will face the same fate in a year or two, and there is still a queue of orders for them."

"But the supply of aircraft is possible," Kornev added. "At one time, Russia sold MiG-29 and Su-30 aircraft to Philippines' neighbor Malaysia. Over time, we could even supply Iskander-E, which Russia has sold only to Armenia in the past."

For her part, Larisa Efimova, professor of Asian studies at Moscow State University, suggested that President Duterte's foreign policy pivot was only logical, given the history of the country and his own personal background.

"Since the Philippines was a US colony for a long time, Washington pursued a policy of 'Americanization' of the country's socio-political life and mentality. In part, this succeeded. They educated the intelligentsia, which comes from a culture of large landowners of Spanish influence on the one hand (Spain was the Philippines' master for three centuries) and Chinese entrepreneurs on the other."

Ultimately, Efimova suggested, ordinary Filipinos are no longer interested in maintaining the paternalistic relationship between their country and the US. "Duterte deliberately aggravates things, calling his opponents names in order to emphasize the country's independence. He intends to follow further on this course. But in order to counterbalance US influence, he needs Russia. The more great powers are involved, the easier it is to maneuver between them."