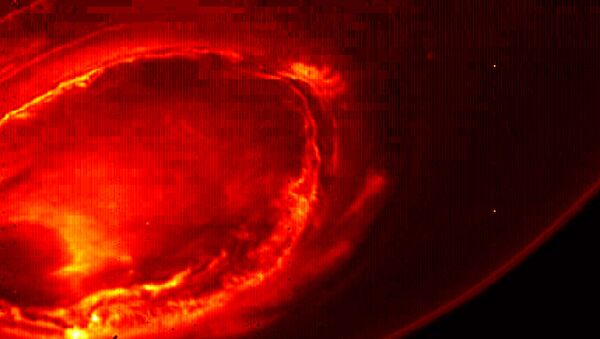

NASA's Juno probe finished its first orbit of Jupiter in late August, and the Waves recording device from the University of Iowa was on it, capturing radio discharges from the planet’s massive auroras. Jupiter's auroras are similar to the Earth's northern and southern lights, but Jovian electromagnetic storms are far bigger, and these lights never go out.

Radio emissions from Jupiter's auroras can be kilometers-long and cannot be heard by the human ear in a natural setting. University of Iowa scientists have "downshifted" them in sound files, Bill Kurth, University of Iowa research scientist and co-investigator for Waves, said in a story for the Iowa Now website. They like to listen to the auroras wailing, he said; and they figure other people might enjoy it also.

Jupiter's auroras, just like the Earth's, are created by atoms and molecules in the atmosphere being hit by charged particles from the sun, causing the electrons in those atoms to become excited, becoming high-energy orbitals; then relaxing back into low-energy orbitals, and, in the process, emitting the entrancing atmospheric light show.

"Waves detected the signature emissions of the energetic particles that generate the massive auroras that encircle Jupiter's north pole," Kurth told Iowa Now. "These emissions are the strongest in the solar system. Now we are going to try to figure out where the electrons that are generating them come from."

Kurth and fellow researchers want to find out how electrons and ions speed along the magnetic field lines around Jupiter. The software detection protocol will do that by sampling plasma waves along those magnetic field lines.

Kurth likens these plasma waves – sets of interconnected particles and fields that repeat like waves – to a plucked violin string.

"The vibrating string is like the plasma itself; in the plasma it is the charged particles that are moving," he explained.

The August pass, 2,600 miles above the planet, is the closest Juno will get to Jupiter, after its five-year, 1.7 billion mile journey to the planet.

Thirty-five more orbits are planned before Juno's mission ends in February 2018 with a fatal exploratory plunge into the atmosphere. The next Waves measurement will occur November 2.

"Jupiter is talking to us in a way only gas-giant worlds can," Kurth remarked.