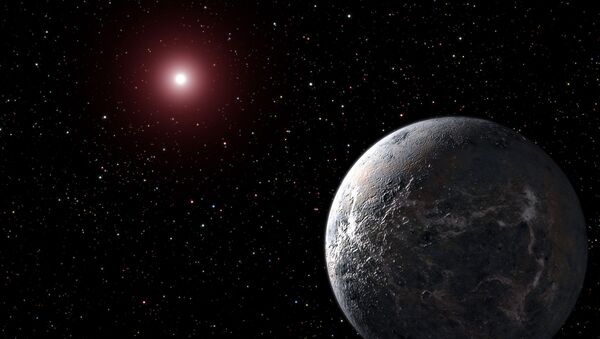

Earth is the only planet we know of that supports life. In looking for life elsewhere in the universe, astronomers and astrophysicists generally seek planetary bodies similar to our own. Those with a similar size and a similar distance from its parent star are believed to offer the best chance of supporting liquid water, a factor deemed necessary.

But one ingredient may be a little more flexible. While Earth circles a yellow dwarf, new computer simulations show that, statistically, smaller red dwarf stars have a greater chance of hosting habitable planets.

"Our models succeed in reproducing planets that are similar in terms of mass and period to the ones observed recently," said Yann Alibert of the Swiss NCCR PlanetS and the Center of Space and Habitability (CSH), according to Phys.org.

"Interestingly, we find that planets in close-in orbits around these type of stars are of small sizes. Typically, they range between.5 and 1.5 Earth radii with a peak at about 1.0 Earth radius. Future discoveries will tell if we are correct."

The study also estimates that planets within the habitable zone of red dwarfs are likely to contain massive amounts of water and deep oceans. Still, while water may necessary for life as we know it, it could also be detrimental.

"While liquid water is generally thought to be an essential ingredient, too much of a good thing may be bad," said co-author Willy Benz.

Red dwarfs have a lower mass than our Sun, requiring the habitable zone to be much nearer. Red dwarfs are also more common throughout the universe and, crucially, easier to detect.

"Habitable or not, the study of planets orbiting very low-mass stars will likely bring exciting new results, improving our knowledge of planet formation, evolution, and potential habitability," Benz said.

Last week, a separate study identified a new promising swath of space in which to track down exoplanets. Known as the Carina association, it contains a red dwarf star dubbed AWI0005x3s.

"Most disks of this kind fade away in less than 30 million years," said Steven Silverberg, a graduate student at Oklahoma University and lead author of the paper detailing the discovery.

"This particular red dwarf is a candidate member of the Carina association, which would make it around 45 million years old. It’s the oldest red dwarf system with a disk we’ve seen in one of these associations."