Prophetic words about the pitfalls of a rushed European integration and enlargement, spoken 35 years ago by one of the most distinguished British politicians, Sir Geoffrey Howe, chancellor of the exchequer in the first government of Margaret Thatcher.

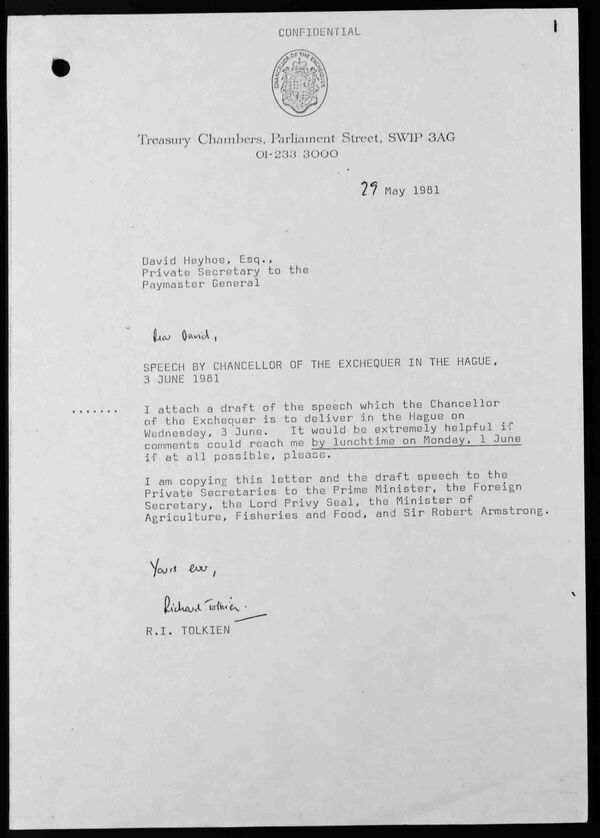

In their first release of classified files from Her Majesty's Treasury to cover the entire period of a chancellorship, the National Archives at Kew, West London, have put out drafts of a speech by Howe delivered to a joint meeting of the European Movement and the Foreign Affairs Institute in The Hague, on June 3, 1981.

"My main concern is for the future of the Community."

Howe's worry was that the European Community (EC, predecessor of the EU) members were locking horns in two bitter disputes: how to remedy the distortions of the Common Agricultural Policy and how to correct the budgetary imbalances between member states.

"The problems arise because the Community's arrangements make no provision for the relationship between the contributions and receipts of individual member states. There is no provision to ensure that the net balance of contributions and receipts for each individual member state is defensible."

And it did indeed prove indefensible during the Brexit debate in the UK, when complaints about paying more into the Brussels coffers than Britain was getting from them swayed the public opinion in favor of leaving the EU. Howe laid the blame for this inequity at the doors of the European institutions.

"The net effect of the budget on individual member states is largely fortuitous. It emerges accidentally from a multitude of separate, uncoordinated decisions by the Commission and the Community's specialist councils."

"In the original Community of six, this incompleteness in the Community's financial arrangements did not pose a serious practical problem," Howe accepted. However, he warned, "the Community's budgetary problems will become more acute as a result of enlargement."

Howe reminded his Dutch audience that "at the time of the accession negotiations in 1970, the British government expressed concern that the combination of budget imbalances and flawed Common Agricultural Policy would place an impossible burden on the UK, which could not be solved by transitional arrangements." There were great ambitions for economic union in the Community. Even then, however, the Community recognized that, if things turned out differently, an ‘unacceptable situation' could arise and would have to be remedied. The Commission paper of October 1970 stated:

"… should unacceptable situations arise within the present Community or an enlarged Community, the very survival of the Community would demand that the Institutions find equitable solutions."

Sadly, Howe continued, "many of the hopes and aspirations of the early 1970s have been disappointed." European economies, like those of the rest of the world, have been gripped by recession, and CAP expenditure has continued to consume the lion's share of the budget, thus hampering the development of other important policies. As a result, unacceptable situations have indeed arisen — first for the UK and then for Germany, and so for the Community as a whole.

Erosion of Public Support

"… the problems of agricultural expenditure and budgetary imbalances… are damaging the fabric of the Community," Howe told the Dutch. "There is a real danger that public support for the Community will be eroded, and the progress of the Community halted, if we do not find solutions to these problems."

In fact, Howe said, there has already been "a worrying reduction in popular support for the Community in some member states — by no means only in the United Kingdom."

"The dangers over public support arise partly from the fact that the uncorrected impact of the budget is manifestly unfair, and partly from the absence of any established method of correction short of sustained punch-ups every two years or so. Member states are repeatedly flung into the ring against each other with as little dignity as the contestants in ‘Jeux sans frontiers.' There is a real danger that, in the face of all the unfairnesses and the confrontations, support for the Community will fade away in the net contributor countries. If that should happen in Germany as well as the UK, then truly the Community would be in trouble."

Pretending the dangers are not there, Howe warned, "will damage Community beyond repair."

Why was it that popular support for the Community was so patchy and, in some countries, less than secure, Howe asked.

"There are many who feel… that the Community has in some way been responsible for the economic dislocation and setbacks which followed the two oil price shocks of the 1970s — or is at least responsible for their not having been overcome more painlessly."

Fast forward to the ongoing Eurozone crisis and Sir Geoffrey Howe's words sound more than topical.

Negative Media to Blame

Another powerful cause of the fluctuations in popular support, Howe suggested, was "that there seem to be so many quarrels in the Community. The way media reported Community affairs added to the negative perception: the processes of adjustment, reconciliation and allocation are perceived as battles, or clashes; and strong passions are aroused among politically conscious people in all our countries. People feel that our organization is keeping the countries of Western Europe perpetually at loggerheads with each other."

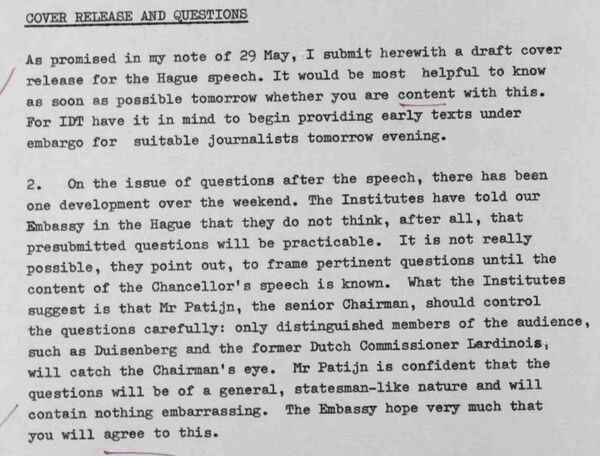

It looks like Howe's speech was considered by the Whitehall mandarins and their Dutch counterparts to be too explosive to give the media a free reign to report it, so a canny damage limitation tactic was devised: the early text would be provided only to "suitable journalists" and "Mr. Patijn, the senior Chairman, should control the questions carefully: only distinguished members of the audience… will catch the Chairman's eye. Mr. Patijn is confident that the questions will be of a general, statesman-like nature and will contain nothing embarrassing."

Speed Limit

Even back then other members of the Community accused the UK of trying to renegotiate its terms of entry into the EC. Howe‘s assurances that "we take no pleasure in that at all" could be read as a tacit acknowledgement that the UK was indeed looking to change its entry terms. "We all hoped that the budget problem which some foresaw would not in fact materialize. But it has materialized, and it has not been solved." Likewise, the problem of immigration from new and poorer members of EU could have been foreseen but came as a shock to EU states when it did materialize.

The EU could have seen Brexit coming long time ago. Britain has been making Eurosceptic noises ever since it joined the community. But the problems she has been complaining about have never been properly addressed, let alone solved by the Brussels bureaucracy, which appears to be living in an ivory tower.

Of course, Brexit was not on the mind of Howe or the government of the day. "We are anxious to see Europe progress still further," Howe told his Dutch audience. "We want to play a full part in that progress. We are proud to be in Europe and of Europe. Without Britain, the Community would be incomplete. Without the Community, Britain would be incomplete."

However, in a metaphor very much reminiscent of the present EU conundrum, Howe said in 1981:

"Our present arrangements can be compared with a computer program which is admirable in every way except that one vital constraint is missing. We ask the computer how fast the traffic should drive through a road tunnel so as to minimize congestion. The answer comes back: 1,000 kilometers an hour! We forgot to tell the computer that there is a limit to the speed at which traffic can move."

It appears that EU bureaucrats to this day don't quite understand that there's a limit to what individual EU member states can sustain or tolerate. Howe's prophetic warning of 1981 was lost on Brussels.