In a punchy op-ed for RIA Novosti, Kosyrev explained that for Russians, "the coming year is set to be a strange one," filled with psychological shocks. Two months ago, the pundit recalled, Russians learned that the US is not filled to the brim with Russophobic propagandists and those who would believe their propaganda. "It turns out that they also have normal people. Moreover, there are a lot of them – enough for them to gather their strength and elect a president. What kind of president he will be is still unclear, but at least one thing is obvious – at least he resembles a human being."

Russians, the Kosyrev suggested, "still haven't fully grasped the significance of this discovery. And we haven't thought about what we should do now – how we should think of America – should we come to fall in love with it?"

Pryor appealed to Americans, asked them what they had done with their country. After all, she said, America, which once "gave us a poetry of democracy that was grand and uplifting," was in freefall. "Roads, airports, an economy, perhaps even a society, falling to pieces." Trump's election, she said, "feels like a sudden plunge" after a gradual decline.

Below that, Kosyrev noted, "there is an appeal from the editors for non-Americans tell NYT how Trump's election has changed their attitudes toward America (if it has changed them)." "A good question deserves a good answer," the pundit said, "even if it's not necessary for it to be in the New York Times."

On the other side of the world from Australia, there was Russia, and Russians, for the most part, reacted to Trump's victory very differently. Most hoped the President-elect would lead to a fresh start for Russian-US relations, or at least reduce the level of tensions between the two countries. Kosyrev's take of things is a bit more complex, and subtle.

@DanaDelany The continuation of the story. Just a package of sugar in the Russian store. Trump is everywhere 😎 pic.twitter.com/mgesoK7RC8

— Julia Kits (@JuliyaKits) 4 января 2017 г.

"But where are we to go from here in our attitudes toward the US?" Kosyrev asked. "Back to the 1960s?"

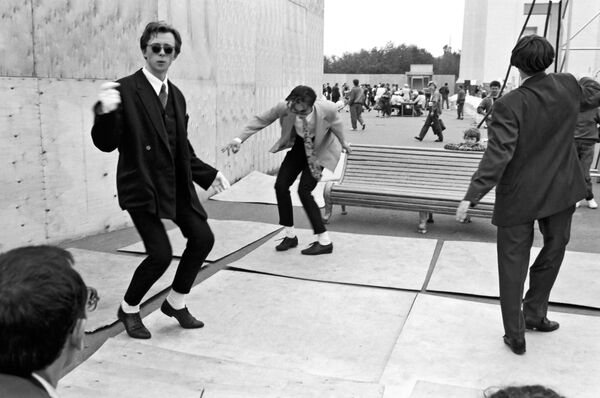

"Back then," he recalled, "there was not so much love toward the US as there was a growing sense of envy, admiration, and an inferiority complex. Soviet propaganda at its best tried to change things, but caused the opposite reaction. The more it tried to convince us that we faced a crumbling society being torn apart by its contradictions, the more Soviet people began reflecting and making their own conclusions."

"For some, the beacon of light was Europe. To others, it was America. Basically, this was a beacon that shone on the other side of the Iron Curtain, where one had to have the appropriate CV to go and visit." After all, it was feared, "one might go and look, and not come back."

"This envious admiration lasted about to the end of the 1980s," the commentator noted, "when the Iron Curtain began to crumble, and Russians went 'over there' to take a look, or get a job. We had a look, and then the wave began to turn in the opposite direction."

"It's difficult to say when this change in Russian sentiment became irreversible, either quantitatively (i.e. for the majority of the population) or qualitatively (i.e. no more illusions). Probably, it was in 1999, following the US bombing of Yugoslavia, after which pro-Western forces and parties no longer had any chances to win any elections in Russia. Today, they don't have a chance to even get a seat in parliament."

And after that, Kosyrev recalled, things only got worse: "war and lies, more war and lies, and so on and so forth until the end of 2016, when things came to a head, and united virtually the whole country [Russia that is] in enmity toward the US. No, not enmity – but worse: a sense of utter bewilderment over the nonsense that was being peddled, all without blinking. But also contempt (liars are always treated with contempt). And even a sense of pity."

"And then Donald Trump appeared, and everything started spinning" in people's perceptions, the analyst noted. "It turned out that we had completely lost contact not with America as a whole, but only with about half of the country. What is to be done? How are they to be hated (or despised) now? Human beings are inert – their thinking is reformed very slowly. Sometimes entire generations come and go, convinced in the rightness of thinking from an earlier era. Change is a painful process."

"For me, it's been easier," the political writer admitted. "Living one floor below me in my apartment building is my American friend Karl Hutchinson. He ran away from America (from his ex-wife, a feminist, who bankrupted him during their divorce). He met a beautiful Chinese woman. He and I occasionally meet for a drink of - let's say tea. And right now we are both celebrating."

Kosyrev continues. "Now, we sit together with Karl and sort things out: 'Dmitri,' he says, 'do you think things will Trump will be easy? That remains to be seen. You'd be better off acting honestly and openly with him.' 'Karl', I respond, 'do you know that attempts at perestroika [restructuring] and overhauls in a relationship can be a dangerous thing? But at least now we have a chance.' 'Dmitri,' he asks, 'do you want to see America become great again?'"

"And here I grow pensive. 'Great how?' I ask. 'What do you mean? Like when you developed Operation Dropshot (the plan for the nuclear bombing of Soviet cities immediately after the Second World War)? Or like in the 1920s, when jazz music was all the rage and the US had no problems with the Soviet Union? Or perhaps there is no point in searching for something in the past, and we need to think of something for a new future.'"

"Returning to the New York Times editors' appeal – to explain how my attitude toward the US has changed after the advent of Trump: it's simple. America suddenly demonstrated that it was possible to respect it, or if not all of it, then at least half of it. And even to empathize with it a little. Yes, and to cautiously hope for it to succeed."