A political earthquake happened when Britain voted in a referendum June 2016 by 52 percent to 48 percent to leave the EU, following years of rancor over its membership — particularly within the Conservative Party, which has been divided over membership for years — as well as rising anti-EU sentiment.

Although the UK as a whole voted out, Scotland and Northern Ireland voted to remain, which has thrown the whole matter into chaos. Scotland narrowly voted to remain a member of the United Kingdom in a 2014 referendum. The EU vote has brought calls for another independence referendum in order for Scotland to remain part of the EU, outside of England and Wales.

Meanwhile Northern Ireland has its own issues with the result — not least because it has benefited most from EU membership, receiving billions in various subsidies or relief programs. It is also in a state of political flux, with the delicate arrangements for government — arrived at as part of the Northern Ireland peace process — in the balance, following a row between the two main parties.

Afterthought

Article 50 of the Treaty of Lisbon was probably an afterthought, following months of negotiations and midnight oil sessions. It simply states: "Any Member State may decide to withdraw from the Union in accordance with its own constitutional requirements."

But it was never going to be a simple as that. UK Prime Minister Theresa May wanted to give notice under Article 50 by herself — acting as PM of the majority ruling government of the day — using what is known as the Crown Prerogative. However, a group of people thought differently and took the matter to the High Court, arguing that May needed to go to parliament to get the assent to trigger article 50.

The High Court agreed with the petitioners in that it was for parliament to vote on the matter and May appealed against the ruling to the Supreme Court, which ruled — January 24 — that: "The change in the law required to implement the referendum's outcome must be made in the only way permitted by the UK constitution, namely by legislation." That meant going to parliament.

They told us #Brexit would save money (which would go to the #NHS), but it's turning out to be very costly. pic.twitter.com/7GBcnzye0q

— Richard Corbett (@RCorbettMEP) 31 January 2017

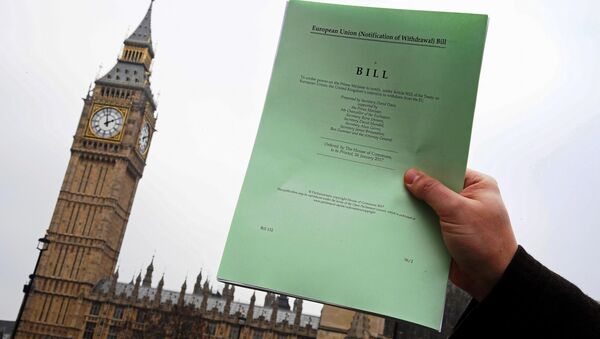

Theresa May's government needs the bill to go through both the House of Commons and the House of Lords quickly and with no fuss and so, has drafted a simple bill. It states that it is a bill to: "Confer power on the Prime Minister to notify, under Article 50(2) of the Treaty on European Union, the United Kingdom's intention to withdraw from the EU." It says little more.

When did #Brexit become an inevitable law of nature? When did an advisory referendum become Holy Writ? When did the UK lose its mind?

— We Need EU 🇪🇺 (@WeNeedEU) 31 January 2017

However, the issue it what is meant by "leaving" the EU. Some — as in Scotland and Northern Ireland — want to ensure the terms of leaving allows them to continue trading with the EU is a way that continues to suit their needs. Others argue that leaving the EU means remaining part of the European Economic Area or the customs union — just getting rid of the Brussels machine.

Amendment Saga

The bill currently going through — although drafted short and simple — could face a barrage of amendments, now that parliament has been allowed — by the Supreme Court — potentially to meddle with the whole process of triggering Article 50.

Moreover, the legislation could also end up with parliament having to be consulted on every aspect of the negotiations which could take two years or more — depending on another clause of Article 50, which states:

"The Treaties shall cease to apply to the State in question from the date of entry into force of the withdrawal agreement or, failing that, two years after the notification referred to in paragraph 2, unless the European Council, in agreement with the Member State concerned, unanimously decides to extend this period."

Thus, a period of shenanigans in parliament could end up leaving May and her team going to Brussels to conduct an already difficult negotiation with one arm tied behind her back. Many people believe that parliament cannot go against the result of the In-Out referendum on EU membership and the "out means out." But that depends on who you talk to.

MPs: you have reason and right to reject the Article 50 Bill. No alternative to EU membership could ever be as good: #Brexit is folly.

— A C Grayling (@acgrayling) 31 January 2017

The other major issue, which will be up for debate as the bill passes through both houses in the coming weeks, is whether or not parliament will have the final say on whatever new deal May's team at the Department for Exiting the EU can wring out of Brussels. If — at the end of the process — Britain is offered a deal that parliament is not happy with, could they reject the deal and throw the whole matter into further chaos?