In 1917, this revolution, which was a combination of a popular uprising with an elitist anti-monarchist plot, toppled emperor Nicholas II and paved the way for almost a century of "troubled times" in Russia.

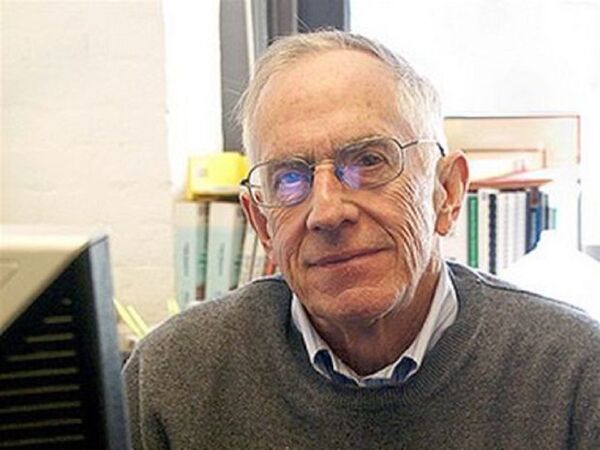

When Nicholas Daniloff was born in a Russian émigré’s home in Paris in 1934, his grandfather Yuri Daniloff, a former czarist general and the head of the Russian army’s headquarters during the World War I, was still alive and had two more years to live. Isolated both from his now Bolshevist Russian motherland and from the majority of his fellow émigré officers, general Yuri Daniloff did not lead a happy life in France.

The generals later said that by forcing Nicholas II to resign they wanted to prevent even bigger troubles, ensuring a smooth transition of state power to the czar's relatives or to the State Duma, the parliament, which was then dominated by anti-monarchist liberals. However, the situation quickly slipped out of the liberals' control, the liberal Provisional Government in October 1917 was toppled by the extremist Bolshevist faction of the Social-Democrat party and a bloody civil war followed in 1918-1921, with 70 more years of communist rule.

"My father Serge, the general's son, lived in the United States a life of a refugee. In early 1917, the Provisional Government sent Serge on a diplomatic mission to Europe, but after the Bolshevist coup he did not want to serve this "new Russia," Nicholas Daniloff remembers. "The members of the mission divided its funds among themselves and went different ways. So, thanks to the February revolution I became an American and later worked as a foreign correspondent in Moscow in the early 1960s and in 1979-1986 – against the will of my father, who said even my American passport might not protect me."

Speaking Russian like a native, Daniloff retains a somewhat distanced and critical approach to his historic motherland. In a curious way, this attitude reflects the divisions that to this day plague Russia when the February revolution is mentioned. "I agree with [a nineteenth century French critic of Russian monarchy marquis Astolphe] de Custine when he said back in 1840 that Russia was doomed to following the West, but never quite catching up with it," Daniloff told me during our first meeting in 1991. "Will this new attempt by Russia to make it (Daniloff meant Gorbachev's perestroika – D.B.) be successful? Russia already had the Great Reform of 1861, the February revolution of 1917. These attempts were well-intentioned, but never quite successful."

In Russia, Daniloff's largely positive view of the February revolution's intentions is shared by the pro-Western Yabloko party, whose leader Grigory Yavlinsky supports the return of Crimea to Ukraine and views the expansion of the European Union to Russia's borders as a positive phenomenon.

"The people who suddenly found themselves having power in February 1917 were educated and honest men, they didn't deceive their country, did not rob it of its riches," Yavlinsky wrote in an article dedicated to the anniversary of the revolution, whose centenary is coming on February 23. "They just lacked the needed experience of running the state affairs, they had been denied this experience by the authoritarian czarist regime."

Vyacheslav Nikonov, dean of the history department of the Moscow State University, has a more negative view both of the February revolution and of its leaders. "The people who held power between February and October 1917 were irresponsible and unpatriotic. The first thing they did after coming to power was to liquidate the police department at the interior ministry, a step that led to a quick rise in violent crime and extremism. The old czarist governors were all dismissed or even arrested, without clear guidelines being given as to how the citizens should elect the new governors.

Nicholas II and all of his family were executed by the Bolsheviks in 1918, a little more than a year after the February revolution. Most of the military participants of the anti-Nicholas plot (including general Nikolay Ruzsky, who had the immediate influence on Nicholas during the latter's abdication) were killed by the "revolutionary masses" already in 1917-1918.

The politicians involved in the anti-monarchist conspiracy at least since 1915 (Duma leaders Pavel Milyukov and prince Georgy Lvov, industrialist Alexander Konovalov) later lived more or less comfortable lives in emigration, as Russia was treading its bloody path from the civil war to Stalin's collectivization.

Some participants of the February events (like the more moderate Duma member Vasily Shulgin) outlived even the 1941-1945 Great Patriotic War with Germany – a dramatic "remake" of World War I, which the February revolution is widely believed to have prevented Russia from winning. Shulgin later returned to the Soviet Union, where he spent many years in jail and exile until 1976 (he died at the age of 98), bitterly condemning his Duma colleagues' actions in February 1917.

Was the February revolution inevitable?

During Soviet times even doubting the "historically predetermined character" of the events of 1917 was officially prohibited. Interestingly, the liberal press and academia in Russia still clings to this "fatalist" view. Among those who disagree one may name Boris Mironov, history professor at St. Petersburg State University and an author of several books on the Russian revolution of 1917 (the latest trend is to view both the February and the October coups as parts of the same process).

"There was no inevitability behind the events of February 1917," Mironov said in a phone interview. "Russia was not in a military or economic crisis, the food situation in St. Petersburg was not nice, but it was not worse than in Paris, which had no revolutions after all. Russia's Achilles foot was public opinion, which had been carefully shaped for years by the irresponsible radical intellectuals."

Investigations by both the Provisional Government and the Soviet Chekists later never found any traces of this "treason." In a phone interview, Mironov expressed hope that modern Russian authorities would learn the lessons from 1917, paying adequate attention to public opinion and developing healthy pluralism in the political system, making it more flexible and better prepared to sustain all kinds of pressures.

The views expressed in this article are solely those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official position of Sputnik.